OSU research shows compounds found in hemp can prevent entry of COVID-19

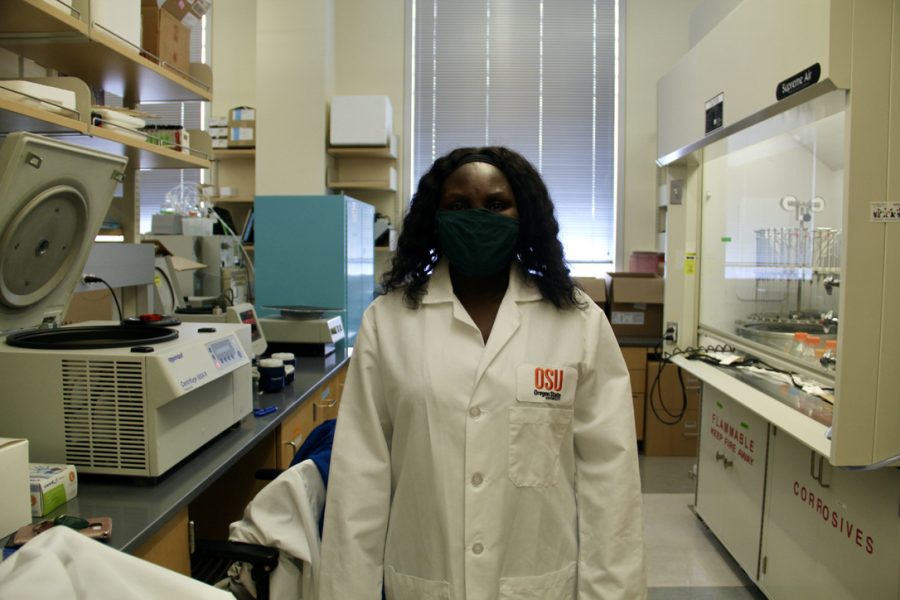

Ruth Muchiri, the research and development lab manager, stands in Van Breeman’s lab. Van Breeman and his team have found that cannabinoid acids can help block the COVID-19 virus from infecting humans.

February 16, 2022

Researchers at Oregon State University found that a pair of cannabinoid acids can bind to the COVID-19 spike protein and block the virus from infecting human cells.

According to Richard Van Breemen, a doctoral researcher and professor of pharmaceutical sciences at the Linus Pauling Institute and College of Pharmacy, this study was initiated midway through 2020 after a screening of botanicals dietary suppliments, which are plant-based substances, for a compound that would affect the entry of COVID-19 into human cells.

The study eventually found three compounds in hemp that bound to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein as potential cell entry inhibitors.

“Prior to COVID-19 pandemic, we were profiling secondary compounds in hemp extracts in collaboration with OSU Global Hemp Innovation Center,” said Ruth Muchiri, the research and development lab manager. “When COVID-19 forced lab closure in 2020, we were looking for a project that would be essential to allow our lab to remain active and contribute towards the ongoing effort to fight the virus.”

Van Breemen said cells of COVID-19 must bind to a specific protein on human cells to begin cell entry and infection.

“By blocking this key interaction of a virus surface protein with a human cell surface protein, infection is inhibited,” said Van Breemen. “Hemp compounds like CBDA and CBGA, which block cell entry by SARS-CoV-2, might be useful for preventing COVID-19 infections in people recently exposed to others testing positive.”

This is just the first step in the beginning of research, according to Muchiri. Next steps might include clinical trials to determine if these compounds will help to prevent or treat the illness; as for now they are recommending that the CBDA and CBGA hemp compounds be included in vaccines.

Van Breemen said clinical trials should begin in the next few months. These preclinical trials will prove the efficacy of what was discovered.

According to Timothy Bates, a doctoral candidate in molecular microbiology and immunology, and Muchiri, there is a long history of the use of cannabinoids in people, including medicinally, which increases the likelihood that the use of these compounds will be safe and effective.

However, Bates said they have yet to determine if a reasonable dose of the cannabinoids relative to body weight will have the desired effect in humans. According to Muchiri, the study was done on cells in vitro—which are cells that are isolated from typical biological context, such as in a petri dish or test tube—and involved testing these compounds in live virus cells.

“While we haven’t performed mouse studies or clinical trials as part of this research, cannabinoids certainly have a long history of use by humans, and are already approved to treat some other conditions,” Bates said. “CBDA and CBGA are less frequently studied in pure form than some of the more well known cannabinoids, but they are likely present in many of the complex mixtures and extracts that have been studied.”

Bates also noted that the research is at times made more complicated by the fact that many of these compounds are illegal. Although Muchiri said these cannabinoids do not have psychoactive effects, and any form of heating such as smoking or vaping will destroy them.

“These compounds may be easily available, but I would not recommend anyone come up with their own treatment plan, or listen to anyone that claims to have developed one,” Bates said. “Despite these promising results, we just don’t have enough evidence yet to know for sure whether this will treat or prevent disease at a safe and reasonable dose.”