Editor’s Note: This is a column and does not reflect the views or opinions of the Daily Barometer

Does anyone care about the Walt Disney Company’s Centennial at Oregon State University?

Well, I do, to a degree. Though that might have more to do with me being a cinephile, and especially so for animation.

To me, animation is the ultimate form of filmmaking, where as long as you can imagine it and draw/render it, it can be real. The Walt Disney Company, the oldest animation studio in the world, turned 100 years old last year.

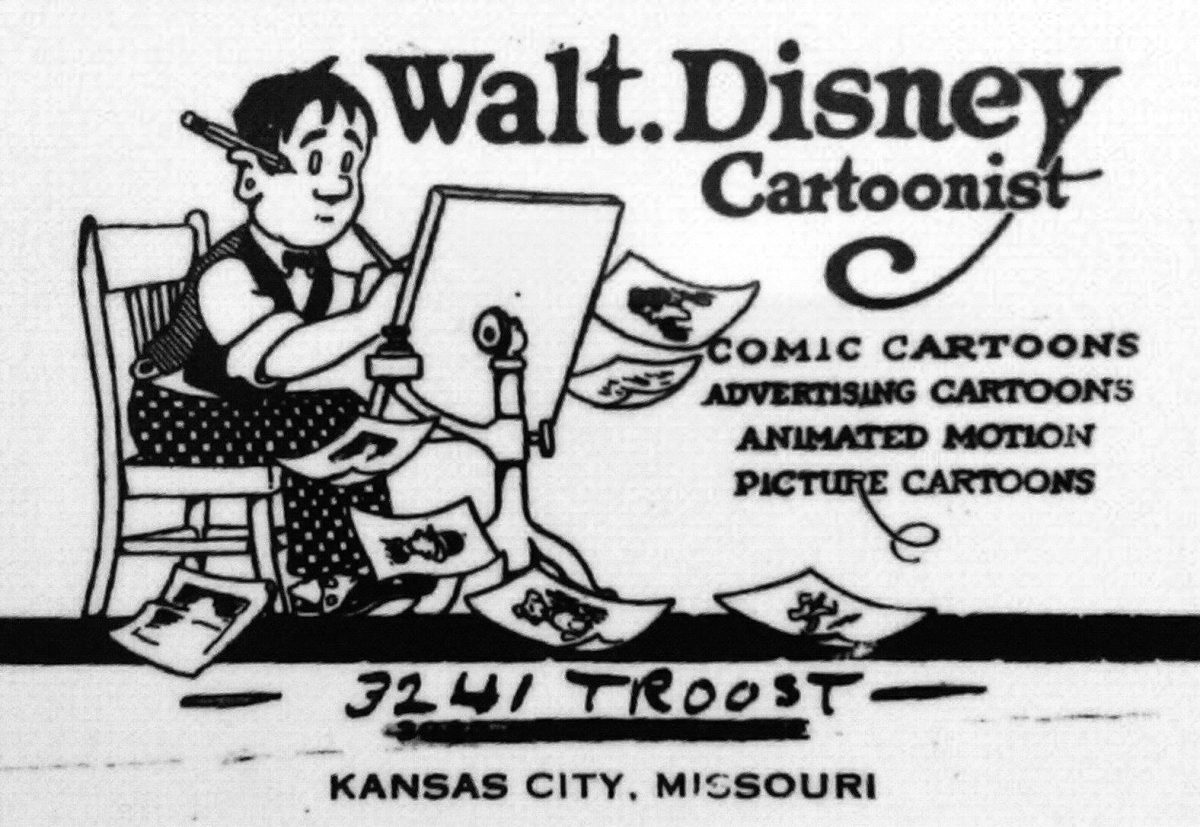

And that is no small feat to achieve. Many animation studios have closed their doors in not even half that time. In fact, Walt Disney’s own first studio, Laugh-O-Gram Studio, folded after only two years due to bankruptcy, though being based in Kansas City probably did not help.

As Jon Lewis, a distinguished professor at Oregon State who specializes in film history, put it: “One of the amazing things about (the company) Disney is its resilience.” And indeed, Walt himself was resilient enough, or perhaps stubborn enough, to found his new studio in Hollywood the same year his first one back in Kansas City folded.

If the company had only relied on animated films, they may have gone the way of their competitors, most of which had folded by the 1980s.

“When the market for animated features faltered, Disney diversified – in 1955 they got into the theme park and television production business,” Lewis added, referring to a decline in interest in animated films that began in the late 1950s and continued until Disney itself revived interest with the film “Who Framed Roger Rabbit?” in 1988.

“After Walt and his brother died, the company faltered again only to be rescued by … the expert leadership of Frank Wells and Michael Eisner,” Lewis said.

Unfortunately, after Wells’ death in a helicopter crash in 1994, a power struggle between Eisner and animation studio head Jeffrey Katzenberg, would cripple the studio again.

But as Lewis said, the company is resilient. After Eisner’s ousting in 2005, his successor Bob Iger, would again bring Disney back into financial security, albeit with some questionable methods.

But that brings us to now, Disney’s Centennial; and what was quite possibly their worst financial year at the box office.

That questionable method Iger used to keep Disney above water was buying up other studios; making them an arm of the Walt Disney Company in a way that seems somewhat monopolistic.

With more studios under the company’s umbrella comes more films being released with Disney’s name on it and, in theory, more money coming back to the company. But first, those films have to make money, and this year all but one of them did not.

With the exception of “Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3,” released in May 2023 and which made $845 million against a $250 million budget, every other major release under the Walt Disney Company’s umbrella bombed at the box office.

For context, it is generally assumed a film must make at least 2.5 times its budget to break even, and even more to be truly profitable, according to Movieweb.

Among those bombs were fellow Marvel Cinematic Universe film “Ant-Man and the Wasp Quantumania” ($476 million gross vs. $200 million budget), and the Walt Disney Animation Studios’ “Wish” ($209 million gross vs. $200 million budget) which was meant as the company’s centennial celebration film; billed by its marketing as a film “A Century in the Making.”

It seems that the Walt Disney Company is facing another moment of crisis. According to Reuters, layoffs are supposed to be coming to the company this year, specifically at Pixar.

Part of this likely has to do with a declining perception of the Walt Disney Company. Its business practices since Iger’s ascension to leadership have become more visible, and a company with a negative image is not exactly going to be frequented.

“Honestly, I’m not the biggest fan of Disney in general,” said Jon Reece, the president of Oregon State’s film analysis student club. “Especially their trend of remaking animated movies in live action. To me it feels like creative bankruptcy… Basically everything Disney does (apart from maybe Pixar movies) feels extremely formulaic and joyless in my opinion.”

As an aside, “formulaic” is the most common descriptor I’ve heard for “Wish,” as a pejorative.

“Disney’s refusal to stop milking franchises like Marvel and Star Wars is just tiring at this point. There have been movies I enjoyed, but at the end of the day Disney is just another massive company churning out movies and shows like a production line,” Reece continued.

The only part of Disney Reece spoke fondly of was their dubbing and distributing of films made by Studio Ghibli, probably Japan’s most famous cinematic animation studio.

“(But) that’s more out of appreciation for Studio Ghibli than it is for Disney,” Reece said.

Fittingly enough, Studio Ghibli’s latest film “The Boy and the Heron” (which was distributed in the United States by GKIDS) has been announced as a nominee for “Best Animated Feature” at the Annie Awards, while for the first time the Walt Disney Company has been shut out of the category in a year where they (either through Walt Disney Animation Studios or Pixar) released any films.

And like yet another pie in the face, another film nominated for the Annie Awards’ best is “Nimona;” a film originally made by Blue Sky Studios, Twentieth Century Fox’s animation division.

The film was originally canceled by Disney after their purchase of Fox and shut down of Blue Sky before Annapurna Pictures revived it with Netflix as its distributor. Prior to its cancellation, the film had received pushback from Disney’s leadership due to its LGBTQ+ content, according to an article from Business Insider.

So, a film that Disney tried to kill made it to the Annie Awards while Disney itself got snubbed. If it happens again at the Oscars later this year, there will be no living it down.

Such “slimy practices,” as Reece put it, were among the other things that soured his opinion of the company.

“They censor movies to appease China,” Reece said. “(And) in the past they’ve successfully lobbied to extend (copyright protections) to suit their interests.”

Disney’s properties falling into the public domain has been in the news recently as the copyrights on its first sound cartoon, “Steamboat Willie,” among others expired at the end of last year.

“I can see the appeal of a lot of their movies, but as a corporation they do stuff that’s very off-putting.” Reece concluded. “The artistic work of the people that Disney employs is often very cool, but Disney itself is not all that great.”

That is likely the image a lot of people, especially today’s college students, have of the Disney Company. For all the appeal of their work, the company doesn’t make itself worthy of support.

Disney did not do itself any favors this last year when simultaneous strikes from the Writers Guild of America and Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists paralyzed Hollywood from May to November.

Admittedly, none of the major film studios painted themselves in a great light during the strikes. One unnamed executive was quoted as saying the plan was to: “allow things to drag on until union members start losing their apartments and losing their houses,” according to an article by Dominic Patten, senior editor, legal and television critic for the entertainment publication Deadline.

Meanwhile Carol Lombardi, the president of the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, was quoted as saying that union members were “lucky to have term (temporary) employment,” according to a GQ article.

So now, after a hundredth year that can only be called disastrous, it seems the Walt Disney’s Company’s resilience is being put to the ultimate test. Until this point, a deteriorating public image has never been the cause of the company’s woes.

Until now, there has usually been either cultural disinterest in its products, as was the case with its animated films after the 1950s; or a diminishing quality in its output caused by internal strife, as happened in the late 1990s.

But it’s going to take more than another “Who Framed Roger Rabbit?” or another “Frozen” to fix the company’s public image. In fact, making another one of either might only make it worse.

If the Walt Disney Company is fortunate enough, perhaps in the layoffs that are said to be coming, they’ll leave behind enough people to turn the company’s image around.

Perhaps then the company can make us look forward to another 100 years of Disney, instead of dreading it.

![Newspaper clipping from February 25, 1970 in the Daily Barometer showing an article written by Bob Allen, past Barometer Editor. This article was written to spotlight both the student body’s lack of participation with student government at the time in conjunction with their class representatives response. [It’s important to note ASOSU was not structured identically to today’s standards, likely having a president on behalf of each class work together as one entity as opposed to one president representing all classes.]](https://dailybaro.orangemedianetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Screenshot-2025-03-12-1.00.42-PM-e1741811160853.png)