Students

Nearly a quarter of a million people have graduated from Oregon State University since the first graduating class of three in 1870.

Some, like two-time Nobel Prize winner Linus Pauling or NVIDIA founder Jen-Hsun Huang, have become household names, but many more have made accomplishments worth remembering.

This month, the Barometer takes a look at five past students who left a mark on OSU and the world but are less well known around OSU’s campus.

Florence Holmes Gerke

If you’ve ever visited Portland’s International Rose Test Garden, you’ve seen the work of 1920 graduate Florence Holmes Gerke.

As a student, Holmes Gerke was active in the campus community, having been both a student body vice-president and a varsity tennis player, according to a May 10, 1921 Barometer article. During this time, Holmes Gerke was also a writer for the Barometer, as well as a correspondent for The Oregonian, according to a May 10, 1918 issue.

Holmes Gerke, a landscape gardening major, graduated with honors in 1920. She was one of only two women to graduate that year from the School of Agriculture, according to a June 8, 1920 article.

After graduating, Holmes Gerke served as head of the Portland Park Commission’s Landscape Architectural Department, according to a November 22, 1921 article.

In this role, Holmes Gerke oversaw the design of many of the city’s parks, according to a May 12, 1934 article. Among other achievements, she designed the International Rose Test Garden and Washington Park Amphitheatre.

Douglas Engelbart

“Mice are as common next to computers these days as they used to be in the holes in the wall, but where did the high-tech computer mouse come from?”

This question was asked by a profile in the Oct. 19, 1989 Daily Barometer, and the answer is OSU alum Douglas Engelbart, who first designed it in 1964.

Engelbart, an electrical engineering major, graduated in 1948. After receiving his doctorate from the University of California, Engelbart would spend 20 years at the Stanford Research Institute, where he would work on his goal of, as he put it, “augmenting the human.”

Englebart’s work ultimately resulted in 25 patents, according to the 1989 profile. Among Engelbart’s inventions were the concept of the window, the cursor and, most famously, the mouse, according to a Jan. 24, 2002 article.

“At times it was very discouraging, but then I thought, ‘If I drop it, who else will develop these things?’” Engelbart said in 1989.

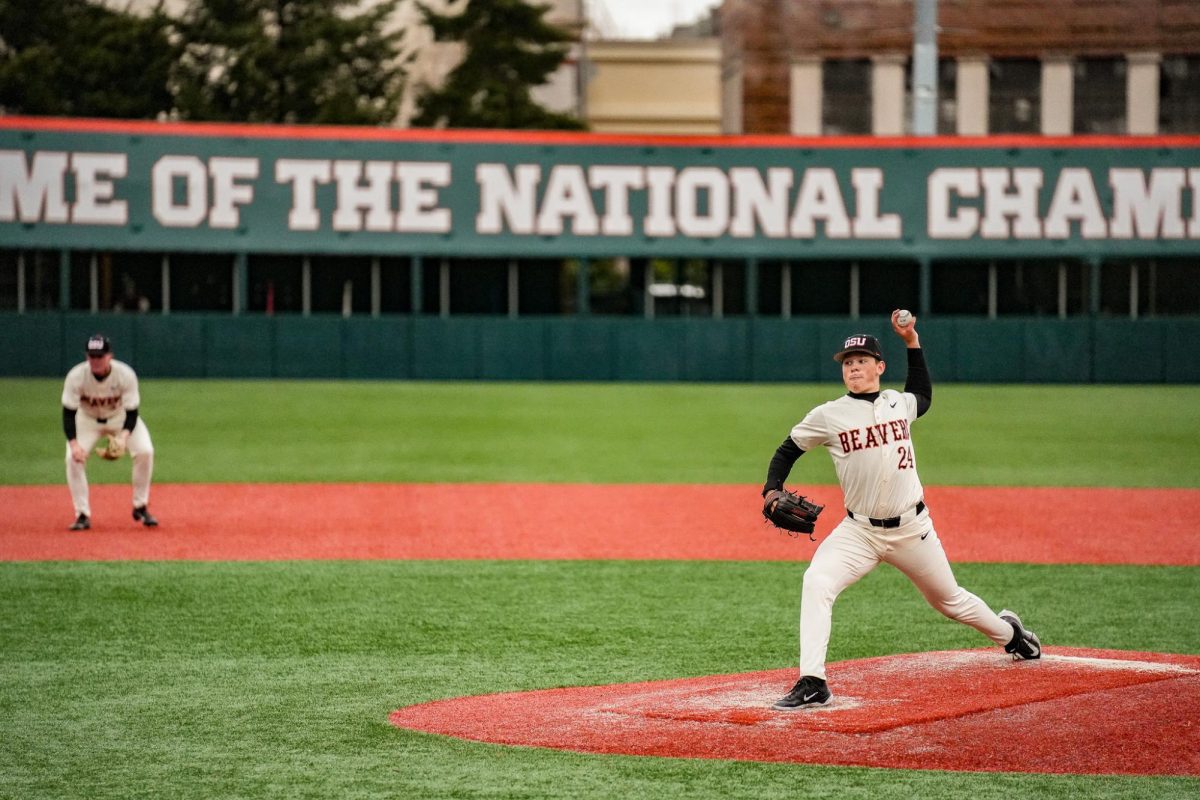

Dick Fosbury

When he came to OSU in 1965, high jumper Dick Fosbury brought the odd technique he’d developed in high school: he went over the bar backward.

While, according to an April 23, 1974 article, track coach Berny Wagner tried to discourage the new technique, the “Fosbury flop” was here to stay.

In 1967, Fosbury set the school record, won his first of three consecutive conference championships and was national champion in 1968 and 1969.

The highlight of Fosbury’s career came in Mexico City at the 1968 Summer Olympics. In front of a crowd of 80,000, he took gold in the high jump with a jump of 7 feet 4 1⁄2 inches (2.24 meters), according to an Oct. 22, 1968 article.

Following his gold medal, Fosbury became something of a celebrity, being called “the most famous athlete in the world right now” by then-OSU sports publicity director John Eggers in 1968. He would also run for ASOSU Senate in 1969, ultimately finishing fourth in his race.

After graduating in 1972, Fosbury worked as an engineer until he retired in 2011 and lived in Idaho until his death in 2023. The technique he pioneered has been used by every Olympic gold medalist since 1980.

Fred Milton

Linebacker Fred Milton played a key role in the 1967 “Giant Killer” Beavers, as the team won big game after big game.

However, Milton’s time as a football star would be overshadowed by events that unfolded in early 1969.

Milton, who had grown a beard, was ordered to shave it or face removal from the team by football coach Dee Andros, who said it violated the team’s grooming policy, according to a Feb. 25, 1969 article. Milton refused, receiving the support of OSU’s Black Student Union, who said the policy infringed on Milton’s rights and freedom of self-expression.

When the order stayed, the BSU boycotted classes. The boycott received support from both Linus Pauling and Dick Fosbury, and according to a March 1, 1969 article, 1,000 students turned out to hear Olympic sprinter John Carlos speak in support as well.

Meanwhile, 3,000 students went to a meeting of coaches and athletes, where Andros said “I have never discriminated against any athlete.” Additionally, 250 supporters of Andros rallied outside the president’s house, and many student-athletes backed the coaches as well.

Finally, on March 5, 1969, the BSU staged a walkout, many leaving for good. According to a March 6 article, the BSU’s 47 Black members walked off campus, and by May 21 OSU’s Black student body was just 17 people, according to that day’s Barometer.

Milton would not return to OSU after the walkout, ultimately graduating from Utah State University, according to a 2021 article.

However, the effects of Milton and the BSU’s stand still remain. According to a June 3, 2019 article, greater diversity in courses, the Education Opportunities Program and the creation of cultural centers can all be traced back to those days in 1969.

Donald Pettit

Donald Pettit may be one of OSU’s fastest graduates, having reached 17,000 miles per hour.

Pettit, however, isn’t a track star, but an astronaut, and he reached these speeds orbiting the Earth on the International Space Station.

Pettit is also an OSU alumnus, who graduated in 1978 with a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering, according to a May 2, 2003 profile.

Octave Levenspiel, a retired professor who taught Pettit, described him in 2003 as inventive, creating “gadgets” such as a heat-absorbing coffee stirring stick that helped the drink cool faster.

“He was unusual. He did things in crazy ways,” Levenspiel said of his former pupil.

Pettit received a doctorate in chemical engineering from the University of Arizona in 1983, and became a NASA astronaut in 1996, according to an Oct. 24, 2008 article. In between, he was a researcher at New Mexico’s Los Alamos Laboratory.

Pettit has completed several missions to the ISS, spending six months on the ISS during his first mission in 2002.

“Explore a discipline you really enjoy,” Pettit advised would-be astronauts in 2003. “Don’t change what you’re studying in school because you think it will make you look more attractive to NASA. Study what you really feel motivated about, be really, really good at it, and apply yourself.”

Professors

Do you know how many professors you’ve had? With how many classes the average Oregon State Student has taken over their college career, you would be forgiven if the answer is no. Combined with the university’s 154-year history, that makes for a lot of forgotten faculty.So, from authors to generals, and everywhere in between, we take a look at four important and influential educators from OSU history.

Ida Kidder

When she arrived at OAC in 1908, Ida Kidder became the institution’s first professional librarian. Over the next 12 years, she oversaw a massive expansion of the library and endeared herself to the student body along the way.

Ida Kidder was born on June 30, 1855 in Auburn, New York, according to a March 2, 1920 Barometer article on her life. After graduating from the University of Illinois in 1906, Kidder moved west, working in both the Washington and Oregon state libraries over the next two years.

In 1908, OAC’s library amounted to 4,264 volumes, according to a Feb. 18, 1975 article on Kidder, and took up a single room in what is now Community Hall. When she died in 1920, the library had expanded to 35,814 volumes and had moved into a new building, today known as Kidder Hall.

In addition, Kidder was involved with the Cosmopolitan Club on campus, spending a lot of time with the school’s international student body.

“Mother Kidder” as students affectionately called her, was widely mourned upon her death on Feb. 29, 1920.

“She held a greater place in the hearts of the students than probably any other one person,” read another March 2, 1920 article.

Bernard Malamud

When he joined the Oregon State College faculty as an instructor in 1949, Bernard Malamud was surprised to find the school didn’t offer an English major.

His advocacy for the expansion of the college’s liberal arts program would help OSC reach full-fledged university status, according to an April 2, 1986 profile. Although his 1961 departure came before Oregon State College became Oregon State University, Malamud’s legacy as a writer goes far beyond a name change.

Malamud’s first novel, “The Natural,” was published in 1952 and would be made into a movie starring Robert Redford 32 years later. His 1958 book “The Magic Barrel” won that year’s National Book Award.

His most famous work was 1966’s “The Fixer,” a novel about antisemitism in tsarist Russia, according to the 1986 article. The novel earned Malamud his second National Book Award, and would also win the Pulitzer Prize.

However, Malamud’s 1961 novel “A New Life” would leave the biggest mark on Corvallis. The novel is set on the campus of Cascadia College, an institution based on OSC, according to a May 5, 1977 interview with the author.

Although critics agreed that the novel’s characters were pulled from real life, Malamud would deny this, saying he was “out to create a fiction and not write about the lives of colleagues.”

“You get your ideas from everywhere,” Malamud said in 1977.

Dawn Wright

The bottom of the ocean is a very deep subject. It’s also something former OSU professor Dawn Wright knows a lot about.

Wright, aka “Deepsea Dawn,” was a professor of geosciences from 1995 to 2011 and a leading expert on both oceanography and geographic information science.

“When people ask me what I do I just say, ‘I make maps of the ocean floor,’” Wright said in a Jan. 14, 2004 Barometer article.

In a Feb. 27, 2004 article, Wright said that ocean conditions can make this challenging, as mapping ships are constantly tossed around by waves. At the time, Wright’s work included mapping newly discovered undersea features.

“It’s very exotic, making maps of places people have never been,” Wright said in the January 2004 article.

For her work on undersea maps, Wright was named a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 2009, according to a Barometer article from Jan. 15 of that year. Meanwhile, for her efforts as an educator, Wright was also named 2007’s Oregon Professor of the Year, according to a Nov. 30, 2007 article.

Since then, her career has reached new heights, with Wright having visited Challenger Deep, the ocean’s deepest point. Today, Wright holds a position as a courtesy professor at OSU.

Mas Subramanian

While inventing a new color may sound like an improbable achievement, this is exactly what Mas Subramanian’s team did in 2009.

Subramanian, the Milton Harris Professor of Material Science in OSU’s Department of Chemistry, and graduate student Andrew Smith discovered a brand new blue pigment by accident in early 2009, according to a Nov. 24, 2009 Barometer article. The pigment was a unique shade of blue, which the researchers said “almost glowed” in a journal article.

“I was pretty surprised when I first saw the color,” Subramanian said in the article. “I had never seen anything like it.”

In the article, Smith explained that they had not set out to create blue pigment, or anything blue at all. Rather, the initial goal had been to create materials for use in electronics.

“When I first took the pellet out and saw the blue pigment I wondered if I messed something up,” Smith said at the time. “The blue pigment was amazing. We decided we had to find out why it was so blue.”

The pigment, later named YInMn Blue, was composed of a mixture of yttrium indium oxide and yttrium manganese oxide, according to an April 7, 2015 article on it. The shade of the pigment can be changed by adjusting the ratio, with more yttrium manganese oxide yielding a darker blue.

Beyond its novelty, the pigment also reflects sunlight, according to a July 11, 2012 article, meaning it wouldn’t trap heat like other dark pigments. Since the creation of YInMn Blue, Subramanian’s lab has gone on to create new shades of other colors.

“Color is something we take for granted,” Subramanian said in 2015. “The more I understand about where color comes from, the more fascinating it is.”

![Newspaper clipping from February 25, 1970 in the Daily Barometer showing an article written by Bob Allen, past Barometer Editor. This article was written to spotlight both the student body’s lack of participation with student government at the time in conjunction with their class representatives response. [It’s important to note ASOSU was not structured identically to today’s standards, likely having a president on behalf of each class work together as one entity as opposed to one president representing all classes.]](https://dailybaro.orangemedianetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Screenshot-2025-03-12-1.00.42-PM-e1741811160853.png)