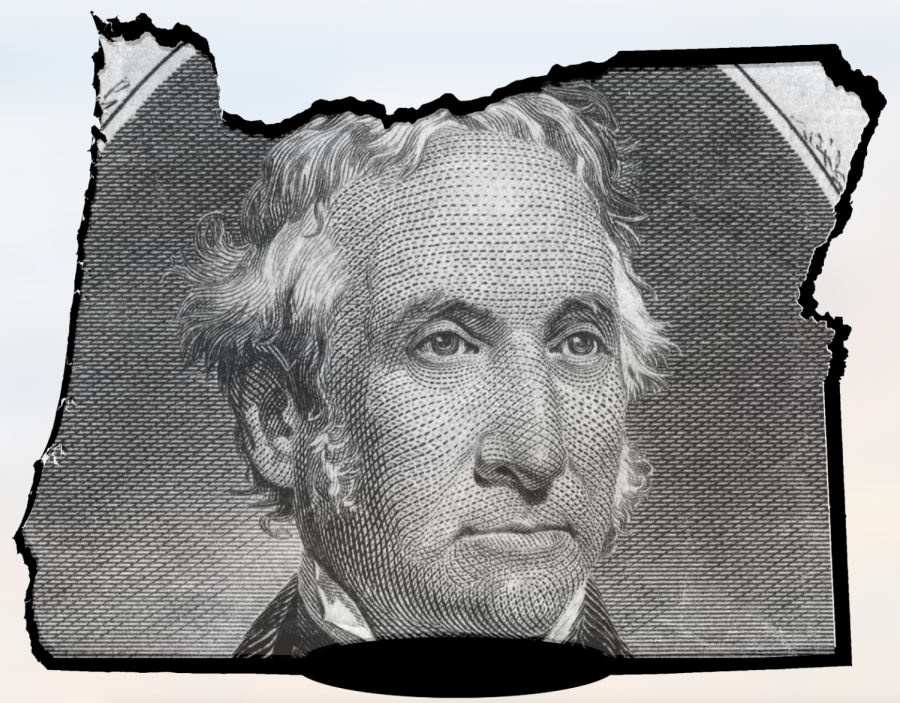

Oregon’s Racist Past: A History

February 11, 2019

Oregon entered statehood as a free state 160 years ago on Feb. 14, 1859. However, its origin is steeped in racial discrimination. A clause of the state’s constitution that was set in place upon its entry in the Union of the United States stated, “No free negro, or mulatto, not residing in this State at the time of the adoption of this Constitution, shall come, reside, or be within this state, or make any contracts, or maintain any suit therein.”

This clause of Oregon’s state constitution is one example of historically racist and discriminatory policies that have been in place since Oregon’s founding as a state. The clause barring African-Americans from residing in the state remained in Oregon’s Constitution until 1926.

“A lot of people forget that. It’s one of the reasons why African Americans are not here, in terms of large numbers, yet they’re in California in large numbers,” said Dwaine Plaza, professor of sociology.

There were also a number of laws and ordinances passed across the state which allowed for legal discrimination against people of color. One example is Lash Laws, which subjected African Americans to lashings if they were found in certain towns or area. Another example were “sundown towns,” which were locations that forbade people of color from being in the town after sunset. As punishment, they were often thrown in jail indefinitely.

Throughout the state, African Americans and other people of color were often times secluded to certain areas of towns and cities. In Portland, African Americans were originally forced to settle in segregated areas of the city such as Albina and Vanport. These communities were built on undesirable lands, particularly Vanport, which was frequently susceptible to floods. In fact, a flood wiped out the community in 1948, displacing the disproportionately African American population housed there.

Furthermore, when attempting to purchase houses, people of color found themselves facing housing covenants — legal contractual agreements within deeds — which forbade them from purchasing or living in certain buildings. Plaza shared an example of these racially restrictive covenants, which stated that a property can only be sold or rented to people of the Aryan race.

“These kind of covenants that were actually in the legal deeds of these places further reinsured the fact that African Americans were not going to be able to occupy certain parts of a city,” Plaza said.

Racial segregation and Jim Crow laws, although mostly evident in the South, were still highly prevalent in Oregon, according to Plaza. Many establishments in Portland were segregated, including dance halls, bars and clubs, and some buildings displayed signs stating that they only served white individuals.

Oregon’s history of racism and discriminatory policies have lingering impacts which are still seen today. Impacts of redlining and discriminatory housing policies are continually felt, particularly in Portland, where many communities of color have become secluded to certain areas of the city. For example, the majority of Portland’s racial and ethnic minorities live in the northeast and east side of Portland.

Natchee Barnd, an associate professor of Ethnic Studies, said it is a challenge convincing young people, and especially people of color, to move to Oregon, consequently impacting the state and Oregon State University’s diversity.

“Even if they do not know the specific histories of racism and violence in this state, they know it is heavily white, largely rural and they have few connections here,” Barnd said via email. “It has never been at the forefront of major anti-racist movements in a way that would draw people of color and indigenous folks to come and feel like they might have a safe and comfortable home here.”

Plaza said that a more modern day phenomenon, such as gentrification, continues to displace and neglect communities of color of services and resources. Even liberal cities such as Portland and Eugene consider themselves to be living in a bubble, according to Plaza.

“People don’t realize that something like gentrification is race and class kind of mixing together, creating opportunities for some and less for others,” Plaza said “They don’t see that as racist — they see that as a natural thing, a want to make the city ‘nicer’.”

Oregon’s racist history is often not a topic of discussion in many public schools across the state.

Barnd said a troubling aspect of neglecting to teach this history in school continues to invigorate and reshape racism.

Andrew Valls, associate professor of political science, said that forgetting history has benefited those who have inherited the advantages from past injustices.

“If we forget the past, and therefore forget the past’s impact on present-day advantages and disadvantages, then it becomes impossible to justify policies that rectify the effects of the past,” Valls said via email.