3-D printing usage sparks controversy

November 19, 2018

The issue of gun control in the United States is as old as the country itself, but modern technology has recently made the debate much more complicated.

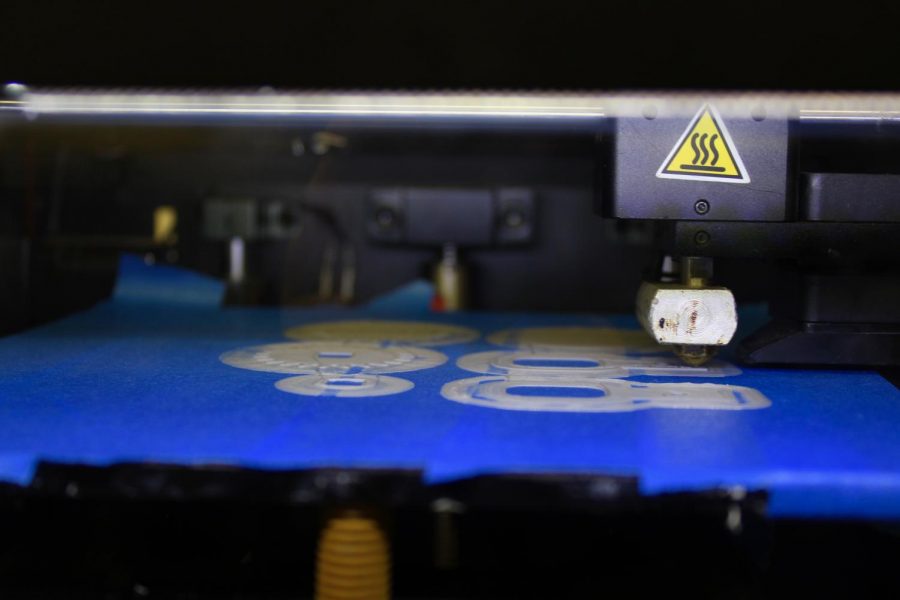

With the advent of 3D-printing, many items that one would have to go out and acquire could now be created directly from home, including weapons, like a gun. At this point in time, however, some familiar with 3D printing are saying fears surrounding damage done by a printed gun are unreasonable.

The first blueprints for a functional 3D-printed gun, the Liberator, a single-shot handgun, were released online in 2013 by a company called Defense Distributed.

Unlike traditional guns, someone does not have to pass a background check to download the blueprints to a 3D-printed gun and print one.

The guns have sometimes been referred to as “ghost guns” because they do not have a traceable serial number.

Within two days, the blueprints to the Liberator were downloaded over 100,000 times, before the United States Department of State demanded the files be removed.

The company sued the department in 2015, and on July 10 of this year Defense Distributed accepted a settlement offer from the Department and were about to resume their work before Western Washington District Court Judge Robert S Lasnik granted a temporary restraining order against the State Department and Defense Distributed, and the blueprints have yet to be released.

Nineteen states, including Oregon, have also filed a lawsuit against the State Department and Defense Distributed.

One might not be able to download the blueprints online directly from Defense Distributed, but the files can still be downloaded from file-sharing sites.

Printing and assembling the parts of a functional weapon is not as easy as it may seem, however, according to Alex Asbury, the current vice president of OSU’s 3D-Printing club.

“At least right now with the market for printers and with the kind of materials you can use, it’s not as big of an issue as I think people think it is,” Asbury said.

Fellow club member Zach Amavisca seemed to agree.

“Theoretically you could. You have a good chance of it blowing up in your hand. That’s the problem,” Amavisca said.

Amavisca said that printing a functional gun would be extremely difficult to do with a home printer.

“[The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives] did print a gun that worked. But the material they had to print it with, you have to do on a $67,000 printer in a shop. Normal printers can’t handle that kind of material,” Amavisca said.

Both Asbury and Amavisca did express frustration over the controversy regarding 3D-printed guns, stating they felt it has not placed a positive light on the 3D printing community.

“I hate how this particular story is giving the whole niche of 3D printing a connotation of something that it’s not even really used for. There’s so much more you can do with a 3D printer and most people aren’t using it for that aspect,” Amavisca said.

Ashbury stated that he also felt that those who intend to create bootleg weapons will continue to find ways to do so, with or without 3D printing.

“3D printing is just another way to make something. The pieces of guns that some hobbists have recreated and have functioned in place of a different piece- those same pieces, you can carve out of wood, or if you have access to a milling machine you can make one on that. 3D printing is just another tool and I feel like it’s being overwatched,” Asbury said.

Asbury also said he does not believe 3D-printed guns pose a current threat to anyone.

“A bow and arrow is more deadly than a 3D-printed gun,” Asbury said.

Despite both Amavisca and Asbury’s claims, some still believe that creating and selling blueprints to 3D-printed guns online is not exactly an ethical business practice.

“From a consumer safety perspective, best practices for product design involve foreseeing all possible uses by customers, including misuse. Second amendment debates aside, and even assuming that all of their customers purchase this product exclusively for legal use, the potential for a hobbyist customer to mis-manufacture or misuse the product is extremely high and the consequences for doing so would be dire,” said Oregon State Business Ethics Professor Keith Leavitt.

Guns are not the only possible 3D-printed product that Leavitt questions the safety of.

“To choose an example more value-neutral than guns, would it be advisable to create a business to help customers manufacture their own pacemakers or other critical medical devices? How would we feel about print-at-home automotive airbags or child car seats?” Leavitt said.

“In sum, I would be inclined to describe (Defense Distributed) as engaging in very questionable business behavior,” Leavitt said.

Oregon State has several 3D printers on campus, including one students can use at the Valley Library.

However, the library’s printer policy states that no one will be permitted to use the library’s printer to create materials that are “unsafe, harmful, dangerous or that pose an immediate threat to the well-being of others” and reserves the right to refuse any 3D print requests.

“We would not print a gun,” Margaret Mellinger, the Director of Emerging Technologies and Services at the Valley Library, said.

For the moment, it appears that a functioning 3D printed gun would be an anomaly, but this may change in the future as technology advances.