Trout demonstrate resilience to wildfire, OSU study finds, but researchers stress more investigation is needed

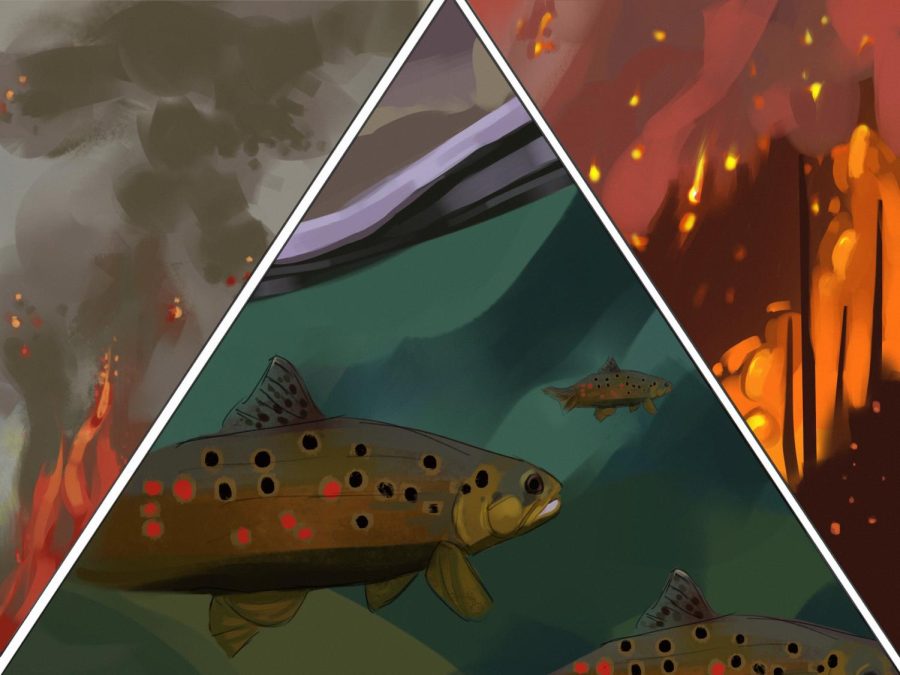

Artist depiction trout swimming in creek with forest fire.

November 3, 2022

Two years ago, all 5,000 acres of the Hinkle Creek watershed burned.

Today, the stream near Roseburg is the site of a study by Oregon State University researchers investigating how resilient Oregon’s trout are to the effects of wildfires.

The study, published in Ecosphere in September, found that while the loss of foliage caused stream temperatures to rise significantly higher than pre-fire levels, trout populations persisted across the summer.

In 2020, the Archie Creek fire burned just over 130,000 acres. For researchers Dana Warren and David Roon, the 5,000 acres that make up the Hinkle Creek Paired Watershed are the ones they’re most concerned about.

“It burned, but a lot of places burned,” said Warren, the study’s lead author and an Associate Professor in OSU’s College of Forestry and College of Agriculture.

According to Warren, what makes this site special is that between 2001-2011, a forest management study was conducted in the Hinkle Creek watershed which collected extensive data on fish and aquatic habitats.

“Fire is inherently a random process,” said Roon, a postdoctoral researcher in the OSU College of Forestry, and coauthor of the recent study. “So to have this long term data set, collected in this watershed that just happened to burn in the Archie Creek fire, is a really rare opportunity for us where we can actually make those pre- and post-fire predictions.”

Hinkle Creek is home to two species of trout. The first is Oncorhynchus clarkii, better known as the cutthroat trout, and the second, Oncorhynchus mykiss, is either a steelhead if it’s ocean-going, or a rainbow trout if it isn’t.

Data from before the fire shows the stream had an average water temperature of around 15°C (59°F). After the fire, stream temperatures were regularly exceeding 22°C (71.6°F), reaching a high of 25°C (77°F).

“Those fish in that system, the previous summer, presumably experienced temperatures that never exceeded 18°C,” Warren said.

According to Roon, this dramatic shift in water temperatures was expected to have a significant impact on the fish.

“Water temperatures in this watershed would have been really cool,” Roon said, “and after the fire we saw this sudden increase in temperature that we assume would have exceeded their thermal tolerance.”

Given the stress the high temperatures put the fish under, the researchers expected the summer heat to take a toll on the trout.

”We expected to see some sort of detrimental effect,” Warren said. “One of the things we were trying to get at initially was…‘OK, they might be able to absorb warm temperatures for half of July…but can they absorb temperatures that warm for all of the summer?’”

In the study, the authors say that they expected to find a decline in both the abundance of fish in the stream, and their condition. However, their findings contradicted their expectations of a decline in population.

“What we found was that there were more fish at the end of the summer in our study region than there were at the start of the summer,” Warren said.

Of course, death is not the only thing that can happen to a trout.

“These initial metrics of persistence…don’t tell us everything about how the fish are doing,” Roon said. “We can look at the size of the fish, we can look at their condition…this last summer we were also tagging fish…so if we recapture fish over the summer we can look at their growth.”

Roon said that while similar studies have been conducted before, data was sparse for regions west of the Cascades.

“A lot of studies on the effects of fire are from Idaho, Montana, Colorado or Wyoming,” Roon said. “Areas where fires are just more frequent.”

“In the west side of the Cascades, we haven’t seen fires of this magnitude in a long time,” Roon said.

According to Renee Davis of the Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board, the land area of the state of Oregon is 61,987,019 acres. Data from the Oregon Department of Forestry shows that 817,782 acres in Oregon were affected by wildfire in 2021, about 1.3% of the state’s total area.

“Fires are essentially becoming increasingly severe, they’re burning at higher frequencies, and they’re burning across larger spatial extense,” Roon said.

With fire on the rise, an understanding of how watersheds and aquatic habitats are affected by it is especially important for a state like Oregon.

“Almost all of Oregon is a watershed of some kind,” said Jason Cox, Public Affairs officer for the Oregon Department of Forestry.

“Any precipitation that falls eventually flows somewhere,” Cox said. it’s hard to think of any land in Oregon that would be outside of a watershed.”

Defining just how many watersheds there are in Oregon is not an easy task. According to Michael Coiner, Communications Coordinator for the Oregon Water Resources Department, “there are countless watersheds in Oregon.”

Coiner says to understand fish habitats in Oregon, look at the number of HUC-8 and HUC-10 watersheds in Oregon.

“To that end, there are 621 HUC-10 and 92 HUC-8 watersheds in the state,” Coiner said.

Watersheds are defined by the United States Geological Survey with a hydrologic unit code, a system which divides the country into a series of increasingly small regions.

According to the Idaho Department of Fish and Game, a watershed with an HUC-8 code is classified as a subbasin, with an average size of 700 square miles, and an HUC-10 is a watershed, with an average size of 227 square miles.

A significant decline in trout population in one of these watersheds would have a significant impact on the local ecosystem, according to Chris Lorion, Native Fish conservation coordinator for the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife.

“A significant decline in salmon or trout populations could impact ecosystems of the surrounding watersheds in several ways,” Lorion said, “including reducing the food supply for many mammal and bird species that prey on salmon and trout.”

While the trout are an important component of the study, Roon says there’s more to the ecosystem that needs to be studied.

“Fish is just one of the pieces,” Roon said. “We’re implementing post-fire monitoring in a lot of those environmental variables that help us provide context of what might be driving those fish responses.”

According to Roon, data collected by the research team includes canopy photos, water samples and measurements of stream flows, as well as getting a sense of prey resources.

They also plan to study other fish and amphibians in Hinkle Creek, including populations of coastal giant salamander and sculpin, a type of fish that dwells in the stream bed.

Warren noted that of the fish species found in the creek, all of them were cold-water species.

“In a system where fish were largely isolated from warm-water species, they largely did fine,” Warren said. “If they were in a system where they were interacting regularly with warmer-water species…then we may have found a very different result.”

While the initial results may be interesting, Roon says Hinkle Creek needs a lot more research.

“The initial observation of persistence through the summer doesn’t tell you the whole story,” Roon said. “Another really important part of this is that we want to track these patterns through time…right now we have funding for four years after the fire. So we still have a couple years left of monitoring.”

However, Roon said his team would be searching for additional funding to ensure they could continue to monitor the creek.

“There’s a lot that we still don’t understand, so it’s going to be really important that we follow up this initial paper with continued monitoring,” Roon said. “To help us understand how these fish are actually responding to fire over time, and what are the drivers behind these fish responses.”

Roon emphasized that the short term results would not be as impactful as long-term research will be.

“We’re really hoping to set this up as a long term study to really get a much stronger handle on how these fish are responding to fire,” Roon said. “That’s going to be important, because fires aren’t going anywhere.”

According to Roon, if wildfires are a permanent issue, then we need to know what impact they’re having on wildlife.

“They’re going to be with us moving forward in time,” Roon said. “Understanding what the implications are for species that we care about like fish is then really important.”