Stories of many lifetimes: Warm Springs Elder works to preserve Native culture and voice with book detailing tribal life

July 3, 2023

As a child, Linda “LaMoosh” Meanus, lived at Celilo Village, across the railroad tracks from the falls and was no stranger to the importance of salmon to her tribe and others in the area.

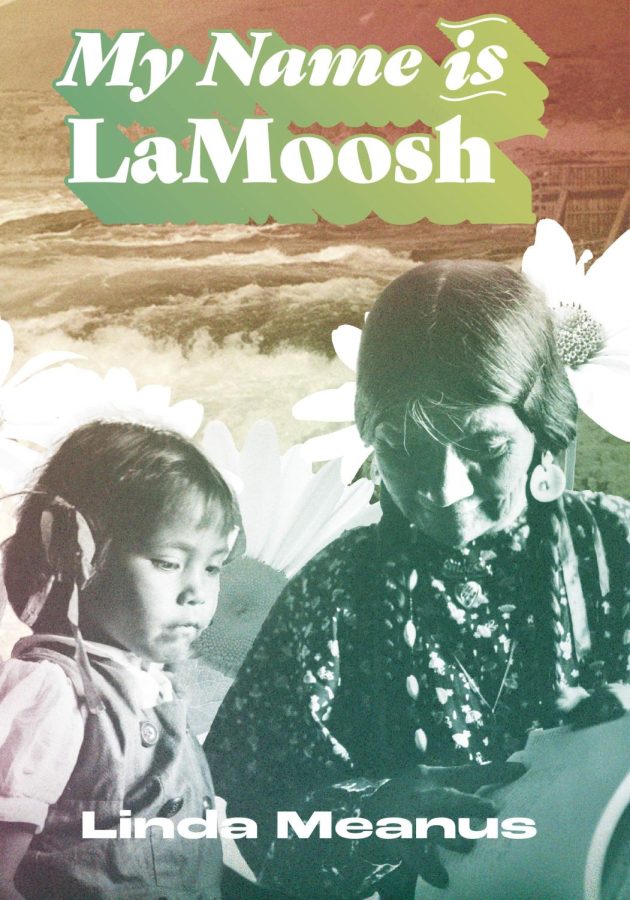

Meanus has recently released a book through OSU Press titled My Name is LaMoosh, detailing her experiences growing up near Celilo Falls as the granddaughter of Warm Springs Chief Tommy Thompson before the 1957 dam completion that destroyed the falls and her village.

Celilo Falls served as a fishery to multiple tribes, and when The Dalles Dam submerged the falls under the Columbia River, these tribes’ way of life was forever changed.

“When they did the dynamite it was like one big ‘boom,’” Meanus said, “The roar of the river just went (to) complete silence. Some of my older elders, they said it was one of the biggest funerals our people had to go through, a big loss.”

According to Meanus, she’d been considering writing a book for a while and was inspired by Dr. Katie Barber, a historian at Portland State University who had written about Celilo previously, as well as linguist Virginia Beavert.

“I always feel good, even though I get emotional, talking about Celilo,” Meanus said. “It gets hard to talk about, but it was important to talk about the way of life and the importance of the salmon before the destruction of Celilo.”

Meanus said she wanted to write a book in part because she finds it necessary to keep sharing her people’s stories before they disappear.

“It was always important to listen to the Elders when they would tell us stories,” Meanus said. “What I talk about, how important our foods and how important our water is in our culture, and I think it’s important to keep it going because I know I don’t want to lose (more). What I already lost was my language, but I’m trying to relearn that. I think that’s our greatest loss, our language.”

According to Meanus, boarding school is part of the reason she lost touch with her people’s language, although she does still have her name. The name “LaMoosh” means Little Flower Floating on a Big River.

Thanks to the government’s pressure, Meanus attended a Catholic boarding school in Lake Oswego, the alternative being placement in foster care.

The Indian Child Welfare Act was not enacted until 1978. Prior to ICWA being passed, thousands of Native children were forcibly removed from their homes and placed in foster care or boarding schools. Approximately 25-35% of all Native children were affected by the crisis, which still has ripple effects today.

In fact, ICWA was recently on the Supreme Court’s chopping block, but was ultimately upheld and is still intact.

At the time of the flood, Meanus was already placed in the boarding school, so she had to watch the event on TV. However, her grandmother came and got the then six-year-old Meanus from school to take her to see the flood site.

“It broke my heart, like my grandfather’s,” Meanus said.

Meanus’ grandfather became chief of the tribe when he was twenty years old and, according to her grandmother’s stories, he lived for their salmon.

“When they destroyed the falls, they gave our people money, but my grandfather tore up his check,” Meanus said. “He didn’t want the money, he wanted our salmon.”

Meanus said she had a good childhood. Her father would spend his days at the river, working on the scaffolding of the fishery, and her mother would load up salmon with the other women of the village to be prepared in a variety of ways, such as smoking or drying.

Meanwhile, Meanus and the other kids would finish their chores and play. They didn’t have TV or school, but Meanus said she was probably better off that way. She said they would play jacks and hopscotch, or marbles and “army” with the boys, and they would make box-sleds in the winter.

“The only thing we did have was a radio,” Meanus said. “We’d always end up listening to Paul Harvey or some of the stories they had, or the music that they played. We had little dance sessions now and then.”

Meanus said she enjoyed her childhood; she was close with her grandparents and would listen to their stories about their life growing up.

“It was important to hear their stories because they weren’t going to be recorded like what I’m doing now,” Meanus said. “I think we’ve lost a lot of our history, a lot of our knowledge and wisdom through our elders that are gone now, so we try to carry that on.”

Meanus said she didn’t realize how complex the publishing process would be, but Confluence, a non-profit that works with Indigenous peoples, and Oregon State Press have handled that for her.

OSU Press Director Tom Booth said it was an “honor” for OSU Press to take part in publishing “My Name is LaMoosh.”

“OSU Press doesn’t typically publish children’s books, but when the team approached Kim Hogeland, our acquisitions editor, she knew that their proposed book had the potential to educate young readers on contemporary Native life in an accessible, enjoyable way,” Booth said. “She saw it as a perfect fit for our mission.”

According to Booth, Hogeland is working alongside several Indigenous authors to publish research projects in the near future.

“Indigenous studies titles are an integral part of our list, books that respect the history, traditional knowledge, and intellectual and cultural property of Indigenous peoples,” Booth said. “Responsible and respectful scholarship is our primary goal, that and the important work of building ongoing relationships with Indigenous groups.”

Recent laws have mandated that Oregon and Washington public schools adapt a curriculum to teach students about Indigenous history and tribes. Booth said OSU Press hopes to see My Name is LaMoosh added to that curriculum for 4th graders.

Lily Hart, digital content manager at Confluence, and project manager for Meanus’ book, said Confluence has worked with Meanus for some time through their Confluence in the Classroom program.

Hart said they bring Indigenous elders and educators into classrooms to speak to kids about their history; in Meanus’ case, she spoke about her childhood at Celilo.

A picture book was previously written about Meanus’ life, “Linda’s Indian Home” by Martha McKeown, who was friends with Meanus’ grandmother. The book is now out of print and, according to Hart, re-publication was a struggle, so Meanus decided to write her own book with “her own voice.”

“She came to us and asked us if we would help her with that project, and of course we said yes because it was a huge honor to be asked something like that,” Hart said. “It really fits with our mission because it’s a way to get an Elder’s voice right into the hands of kids.”

Hart said Confluence tries to be a “venue” for Indigenous voices to be heard in classrooms and public events or even publication.

“I’m just happy that it’s (happening) and I’m happy that people are ready to read this book because I talk from the heart and that’s what we should do, and also listen from the heart,” Meanus said.

Meanus said she does think the younger generations are taking an interest in their culture, and she hopes people will continue helping to preserve Native culture by recording stories and history and keeping the language alive.

“My stories, I think, need to be told and need to be shared,” Meanus said. “I think our kids are really hungry for that kind of story, they want to know about what happened and how life was.”

While Celilo Falls has disappeared under the Columbia River, sonar has recently revealed that they are still intact underwater.

“That was something that they couldn’t destroy, our falls,” Meanus said.