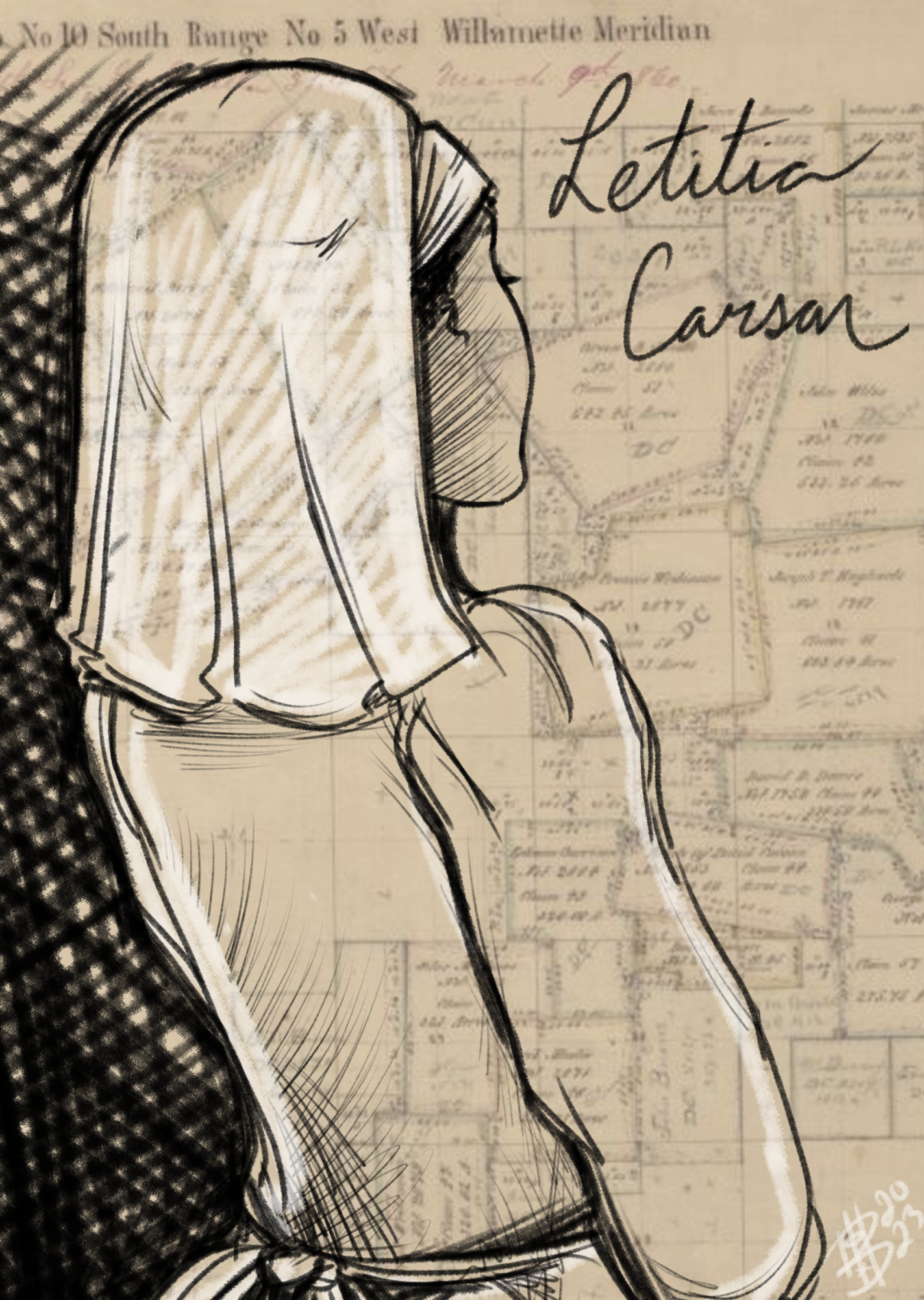

Letitia Carson, a former slave from Kentucky turned Oregon homesteader, is one of the growing diverse stories featured at the Corvallis Museum—showcased through a temporary exhibit—after a refreshed mission statement and a stronger focus on representing all members of the Corvallis community.

Before the Corvallis Museum, the exhibit was featured in the Lonnie B. Harris Black Cultural Center at Oregon State University, but it was something Executive Director of the Benton County Historical Society, Jessica Hougen, absolutely wanted to have in the museum.

According to Hougen, Carson’s exhibit could serve a vastly different audience and even entice students to visit the museum.

The BCHS—founded in 1951—is an organization meant to preserve the history of Benton County, running the Corvallis Museum and the Philomath Museum.

Carson’s exhibit was created by Oregon Black Pioneers, a historical society dedicated to preserving and presenting the experiences of African Americans statewide, due mostly in part by information received from Bob Zybach, an OSU graduate.

“(Zybach) uncovered some of the core findings about Letitia Carson that had not been checked out or researched in probably 100 years,” OBP Executive Director Zachary Stocks said. “So we feel very indebted to the research that Bob and his research partner Jan Meranda conducted together.”

Letitia Carson, as either a slave or former slave, traveled with David Carson – either Letitia’s master or husband – across the Oregon Trail from Missouri, arriving in Oregon in 1845. It was unclear whether David Carson was her husband or slave master, according to the exhibit.

Government-sponsored land claims in Oregon spurred white settlement, displacing the Indigenous population, and giving the Carsons 640 acres in Oregon’s Soap Creek Valley to build a log home, a garden and herd cattle.

This land was later reduced to 320 acres, because the union between the Carsons’ marriage was viewed as unlawful since Letitia was a Black woman.

In 1852, David Carson died suddenly and without a will. Since Oregon’s Black exclusionary laws attempted to discourage Black people from settling in Oregon for more than six months, David Carson’s estate was given to Greenberry Smith, the neighbor of the Carsons.

Carson sued Smith twice, and in 1856 she was awarded a settlement for back wages she was owed for her time with David Carson, as well as legal fees. Sixteen months later, Carson was awarded more money, which included a settlement for the unlawful sale of her cattle.

In 1862 President Abraham Lincoln passed the Homestead Act, allowing an applicant to acquire ownership of government land or the public domain, regardless of race. And in 1869, Carson’s homestead claim was approved by President Ulysses S. Grant, which granted her 154 acres of land and made her the only Black woman in Oregon to receive a homestead at that time.

Carson died in 1888 and was buried in the Douglas County town of Myrtle Creek, at Stephens Cemetery. She left behind two children, Martha Jane and Jack Carson.

Oregon writer Jane Kirkpatrick released A Light in the Wilderness in 2014, a novel based on Carson’s life.

Zybach happened to revive Carson’s story while doing research on Jedediah Smith, a hunter most known for crossing what is now known as Nevada. He found David Carson’s estate because Smith’s trail passed through it.

Carson’s story interested Zybach because in his generation, according to him, “all the history was about old white guys that were writing about other old white guys.” Whenever a woman or person of color was mentioned, it piqued his curiosity.

Zybach was told he was the first person to ask about information related to the Carsons, contained in about 180 documents, because nobody had signed for them since they had been archived in 1856.

With the help of Historian Jan Meranda, Zybach was able to get all the documents transcribed.

“Why (are) these people hidden from our history?” Zybach said.

Zybach has taught classes on Black American history, including Carson’s story, has written newspaper articles on her and even plans on writing a book.

“There are many stories to tell, they’re interwoven, their understanding of them is evolving,” Hougen said. “And we are an organization that is here for the entire community.”

The Corvallis Museum and the Philomath Museum collectively share 140,000 artifacts between each other, including regional and international artifacts. They accept donations from community members, as well as collecting artifacts themselves.

The museum is partly made up of artifacts that were acquired from the now defunct Horner Museum, which operated at OSU.