Editor’s Note: This article contains spoilers for Christopher Nolan’s “Oppenheimer.” This column does not represent the opinion of The Daily Barometer. This column reflects the personal opinions of the writer.

As J. Robert Oppenheimer, inventor of the atomic bomb, stepped out of the limelight, chemist Linus Pauling marched into the political arena as a dominant figure in the science world.

Regardless of the success of his peace activism, Pauling’s role in the history of the bomb remains uncontested.

Christopher Nolan’s film “Oppenheimer” has grossed $850 million at the global box office as of Sept. 3.

The film explores the life, work and political downfall of Oppenheimer, ending promptly in 1959 when politician Lewis Strauss lost his cabinet nomination.

In three hours, “Oppenheimer” packed all the trappings of political drama, scientific exploration and philosophical ponderings, but could only take the audience so far in the saga of consequences unleashed after the bombs were dropped in 1945.

The movie ends on a note of uncertainty. Oppenheimer asks physicist Albert Einstein if he recalls their worry over the bomb starting an apocalyptic chain reaction.

Einstein offers the grave, “I believe we did,” before a grim montage of nuclear weaponry plays across the screen.

Perhaps Einstein and Oppenheimer’s conversation was born of Nolan’s imagination, but it is representative of true, historical fears.

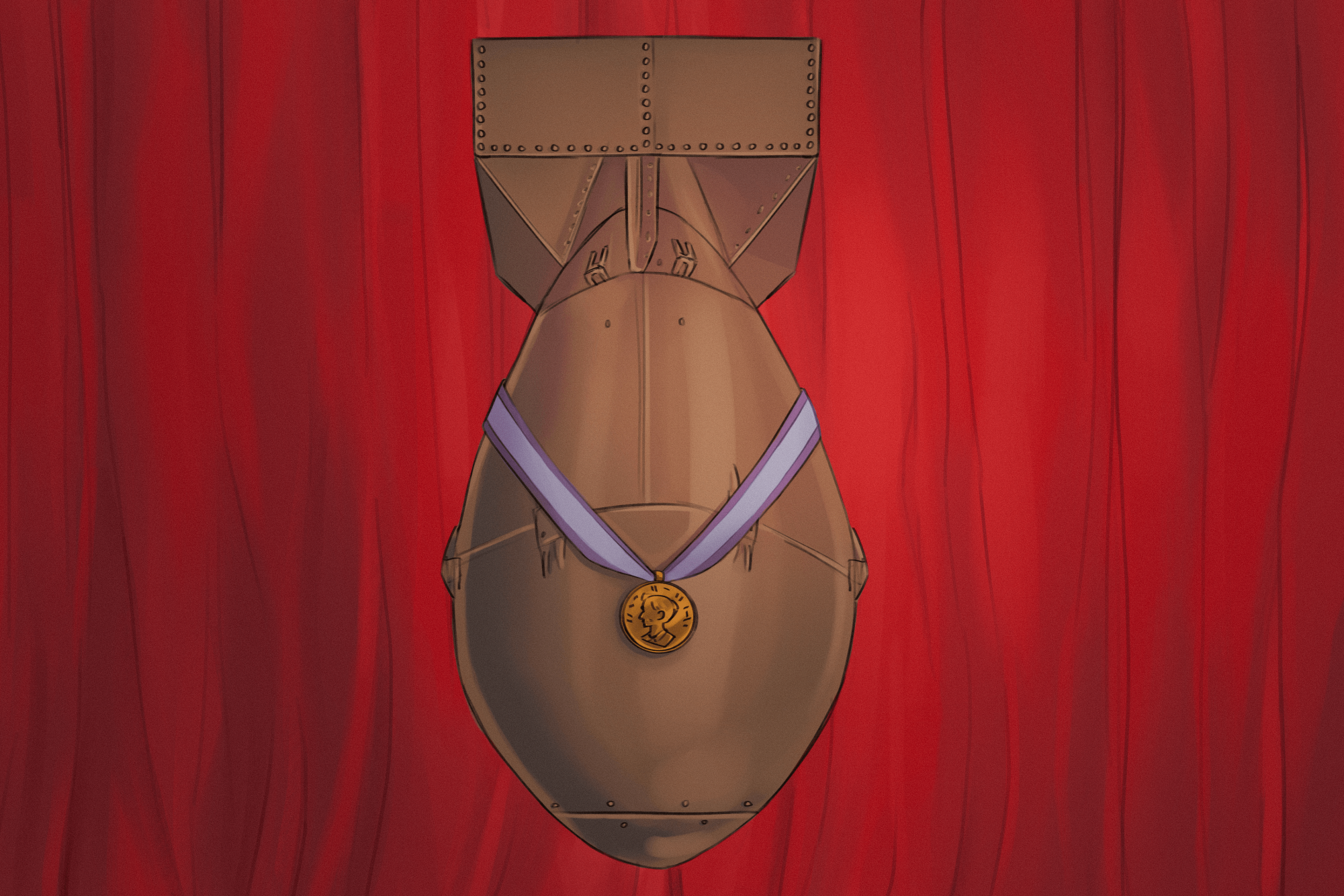

Oppenheimer and the work of the Manhattan Project left the world with an open Pandora’s box, inviting scientists to step into politics and approach the consequences. The most decorated of which was Oregon State University’s own Linus Pauling.

“The fact that he was a Nobel Prize-winning scientist gave him a platform,” said Jacob Hamblin, professor of history and author of “The Wretched Atom: America’s Global Gamble with Peaceful Nuclear Technology.”

Throughout the Red Scare, a widespread panic over the spread of communism and other liberal ideologies at the onset of the Cold War, Pauling not only won a Nobel Prize in Chemistry, but also for peace, for his efforts to ban nuclear testing.

Hamblin explained that Pauling was able to reframe nuclear testing as a question of health for not only American citizens, but all individuals—and those to come.

“His argument was you don’t have the right to test, because it’s not just affecting your own citizens, it’s affecting everybody,” Hamblin said.

Kamil Khan, executive director of Oregon Physicians for Social Responsibility, said in OPSR’s current work in nuclear disarmament, it does not matter who you voted for or what your race is.

“The usage of modernized nuclear weapons will have climate consequences for everybody so the onus is on everybody to get involved in the disarmament movement,” Khan said.

Pauling sued the United States government on this platform and, although the case was dismissed, it gained a lot of national recognition.

“His importance in the international peace movement was cemented in 1957 when he wrote the Appeal by American Scientists to the Governments and Peoples of the World, a petition against nuclear bomb testing worldwide,” said The Pauling Blog, a website run by OSU’s Special Collections and Archives Research Center.

13,000 scientists throughout the world, along with Pauling, signed this petition, which was the basis for his 1963 Nobel Peace Prize.

“What (Linus Pauling) could do that perhaps other scientists couldn’t, was rely on what he learned about quantum mechanics and blend it with what he knew about health… he anticipated in a very serious manner the possible harms. What other scientists saw as risks, he saw as an infringement on human rights, and the rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” said Linda Richards, professor in OSU’s school of History, Philosophy and Religion who teaches History of 20th Century Science as well as directs the Peace Certificate program.

Richards further explained there was a lot of denial from the U.S. Government regarding the safety thresholds for radiation exposure– as long as no one was exposed to a certain limit, the radiation exposure would be negligible to what they’d experience in their day-to-day life.

Pauling was one of the primary scientific voices opposing nuclear testing from 1945 to his death in 1994, although his efforts considerably diminished following the 1963 Test Ban Treaty between the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and U.S.

This treaty prohibited nuclear weapons tests “or any other nuclear explosion” in the atmosphere, outer space and under water.

Richards points this out as an interesting moment in Pauling’s career, wondering why he doesn’t continue fighting for nuclear disarmament as fervently as before:

“Why didn’t he continue? Did he believe we were on track already to abolish nuclear weapons? Was he too busy supporting other peace movements and in his work against the Vietnam War? I still just don’t know enough to know,” Richards said.

Did he even need to continue? With nuclear testing banned by the two largest nuclear forces on Earth, that also eliminated the addition of nuclear fallout into the environment. However, Pauling didn’t necessarily see this as a success.

“The treaty was more for pausing the arms race… only partially concerned with human health,” Hamblin explained.

The question that Linus Pauling challenged the government with was never really resolved.

“One thought I have is maybe because of his involvement researching nuclear contamination, so many other things connect to it, and Pauling got pulled in other directions,” Richards said.

Pauling’s interdisciplinary activist work later in life is illustrative of how the atomic bomb changed the world in all directions.

“Unforeseen consequences” and “atomic bomb” are phrases that often go hand-in-hand, the only certainty was that its ramifications would be enormous.

Much like Oppenheimer, Pauling was flagged by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and politically besmirched throughout his scientific career.

“Pauling wished to collaborate with all citizens throughout the world on the petition, regardless of their governmental or economic system, a position that many saw as a potential threat to U.S. security. Indeed, in the eyes of some, opposition to nuclear bomb testing was equated with being a communist,” The Pauling Blog said.

Upon his death, Linus Pauling and his wife, Ava Helen, had the body of their work archived at OSU.

“It’s a fantastic archive,” Hamblin said. “What’s amazing about the archives is that Pauling didn’t actually work here–he worked at Caltech–so we took Ava Helen’s and his papers to create a much richer collection…noting that it’s “inclusive of a fuller range of his activities.”

The archives are open to students in the Valley Library, which offers digitized versions of many of Pauling’s papers, as well as the Pauling Blog.

![Newspaper clipping from February 25, 1970 in the Daily Barometer showing an article written by Bob Allen, past Barometer Editor. This article was written to spotlight both the student body’s lack of participation with student government at the time in conjunction with their class representatives response. [It’s important to note ASOSU was not structured identically to today’s standards, likely having a president on behalf of each class work together as one entity as opposed to one president representing all classes.]](https://dailybaro.orangemedianetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Screenshot-2025-03-12-1.00.42-PM-e1741811160853.png)