Correction: This story has been updated to correct the name of Marine Mammal Institute founder Bruce Mate.

As a graduate student at Oregon State University’s Marine Mammal Institute, Sheanna Steingass had always wanted to crawl through the carcass of a beached whale.

In November of 2015, the waves off the Oregon Coast washed up the perfect opportunity.

The Marine Mammal Institute, which is also the headquarters for the Oregon Marine Mammal Stranding Network, received a call from the United States Coast Guard about the body of a 75-foot blue whale off the coast of Gold Beach, Oregon.

Now, eight years and two countries later, the whale’s skeleton is almost ready for display at the Hatfield Marine Science Center.

According to an article on ArcGIS, there are approximately 39 blue whale skeletons on display in the world and the one at Hatfield will be the seventh displayed in the United States.

Minda Stiles, the administrative manager and communications coordinator for the MMI, said that MMI founder and past director, Bruce Mate, recognized the event as a rare educational opportunity which spurred volunteers and researchers to the shores of Gold Beach.

“My first impression was, you could smell it before you saw it,” Steingass said, now an affiliate faculty member of the MMI. She added that the stench wafted over half a mile down the highway.

Blue whales, said Steingass, are the largest animal to ever live, and this male weighed about 60 tons according to an article published on King 5 News at the time.

Despite its weight, Steingass said that the whale was noticeably thin with brittle bones that were indicative of a potential nutritional deficiency. Splotches of sun damage and tooth marks left by scavenging orcas scarred its hide. Multiple sources stated that the whale was most likely killed by a ship strike to its head.

Now that it was ashore, Steingass and researchers from OSU, Portland State University and Humboldt State University knew that time was of the essence as decomposition took hold.

According to Steingass, the whale not only smelled bad but as bacteria multiplied, could also pose a serious health hazard to people and animals in the Gold Beach area. Researchers pierced the animal’s stomach before it could explode in the heat. Next, they cut away the blubber in strips to be burned.

“It’s dangerous, you’re slipping around in body fluids … so it was just all about making sure we got those samples and kept people safe,” Steingass said.

Steingass spent most of her time in the mouth of the whale, cutting out pieces of baleen which were sent to California for testing.

After the bulk of the carcass was removed, the skeleton was loaded onto trucks and driven to Newport. There, according to Stiles, it was cradled in fishing nets and lowered by crane into Yaquina Bay, where crab and other decomposers picked the bones clean. Three years later they were lifted and placed in storage while the MMI decided how to get them ready for display.

Frank Hadfield, the CEO and founder of Dinosaur Valley Studios stumbled across news stories of the skeleton through a mixture of luck and a Google Search algorithm which connected his uncle’s last name, also “Hadfield” to the “Hatfield Marine Science Center.”

“I learned that they had just sunk the bones of this blue whale in Yaquina Bay, (and I thought) ‘Wow. (Dinosaur Valley Studios) has a background in that,’” Hadfield said. He reached out to the HMSC, and after obtaining the correct permits, the skeleton was loaded back onto trucks and made its way across the border to DVS’ home in Alberta, Canada.

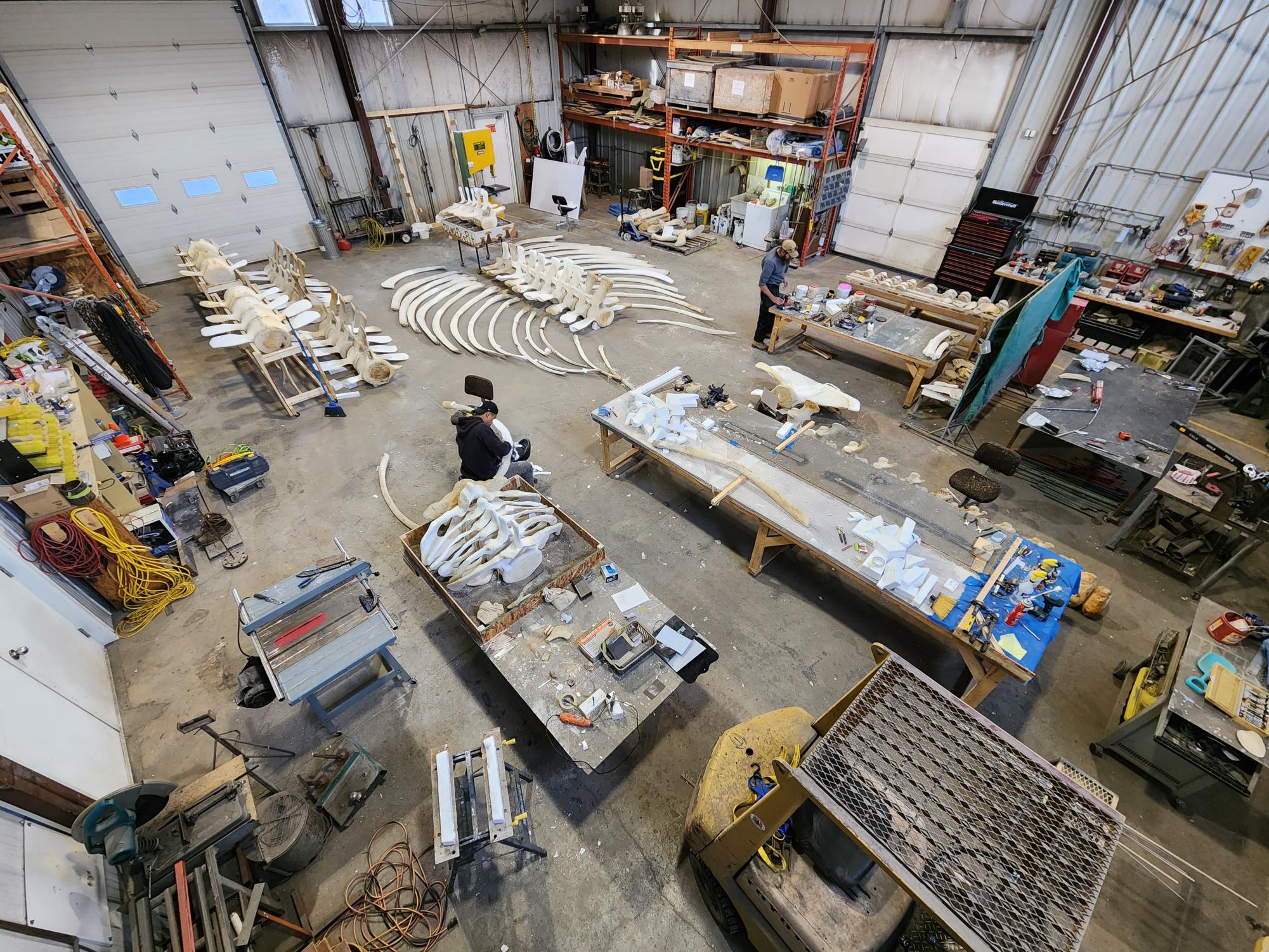

Founded in 2006, Dinosaur Valley Studios does everything from re-articulating fossils to fabrication and prop design. A team of four artists and sculptors took on the blue whale project, said Hadfield, which involved fabricating a full-sized foam replica of the skull which had likely been damaged by the impact of the ship.

“We recommended, rather than reconstructing the cranium which would take a lot of time and money, we could fabricate a replica that would be virtually indistinguishable,” Hadfield said.

The project also involved removing large quantities of oil from the remaining bones. This oil, according to Steingass, helps whales to remain buoyant in the ocean, but if left in the bones for display it becomes rancid. Hadfield said that they avoid the use of harsh chemicals in this process, preferring to soak the bones in warm water for long periods of time and then clean them with hydrogen peroxide.

The company is also building a steel armature which will hold up the skeleton at the display site. Hadfield said that each bone will be held separately so that they can be easily removed.

According to Hadfield, the armature and skeleton are expected to be ready for the journey back to Hatfield at the end of May where Stiles said it will be displayed outside of the Gladys Valley Marine Studies Building.