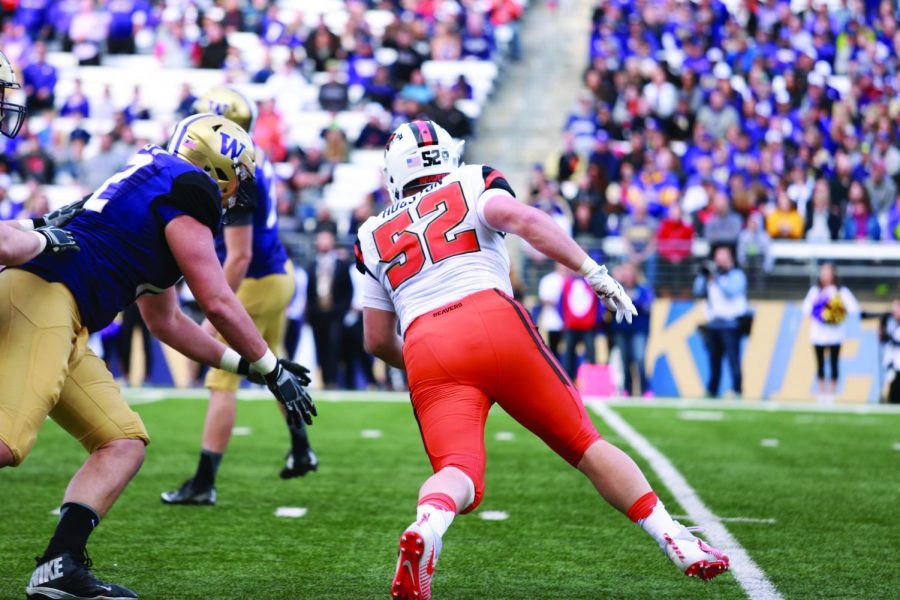

Sumner Houston doesn’t let any obstacle get in his way—and he has the nickname to prove it

November 6, 2016

Sumner Houston took the ball, looked to the rim and rose up for the dunk.

Houston, who is better known as a sophomore defensive lineman on the Oregon State football team than for his pickup basketball skills, had nobody between him and the net.

His ferocious slam dunk — on an indoor Nerf hoop in his Philomath apartment, admittedly — was a bit overzealous; the 6-foot-2, 273-pounder couldn’t stop his momentum and his leg gashed a three-foot hole in the wall.

While others may have laughed the incident off before calling somebody to fix it, Houston got frustrated with himself. He even tried to fix the hole himself, determined to rectify the problem he created.

That’s the reputation Houston has built in his three years at OSU: he’s never one to forget a mistake he’s made, nor will he stop short of remedying the situation whenever possible.

That includes the hoop.

“He was really upset about that,” said fellow offensive lineman Trent Moore, who was Houston’s roommate during the dunking debacle. “He tried to fix it at first and that didn’t quite work out.”

Houston’s carpentry skills may not have sufficed, but his penchant for self-criticism and his unshakable work ethic has led to increased playing time. After redshirting in 2014, he made 21 tackles last season and has five starts this year.

“Football is very important to him,” said head coach and defensive line coach Gary Andersen. “He’s done a very good job of working daily to take what he deems not good — and he’s very hard on himself to the point where sometimes that’s a negative — but really focus on those things. He’s a

tremendous teammate.”

As Andersen alluded to, Houston is his own harshest critic. Sometimes, it almost goes too far. He has a problem letting go of mistakes, which can be his biggest weakness and greatest asset. His freshman year, Houston admits that if he lost a one-on-one drill in practice, he’d “freak out” and struggle to get his mind right for the next drill. Still, memories of past failures are what fuels his drive

on the field today.

Take the final play of the spring game for example. The intrasquad contest took place more than six months ago but Houston still remembers the final play, when his defensive unit couldn’t stop a game-winning touchdown pass. Houston was supposed rush around the right tackle, which he did — but angled too sharply and allowed quarterback Darell Garretson to get outside the pocket.

“It did lose us the spring game,” Houston said. “I hate to lose, all my teammates

know that.”

The fact that Houston still recalls the play vividly is a testament to what sticks with enough to provide motivation. His on-field growth as a result has been apparent the last two seasons. Just ask his best friend and offensive lineman Gavin Andrews, who has spent plenty of time blocking Houston in practice the last few years at OSU as well as beforehand. Houston’s De La Salle High School is rivals with Andrews’ Granite Bay High School.

Houston is a couple years younger than Andrews, so their initial face-offs in practice two years ago pitted Andrews as a starting offensive lineman and Houston as

a redshirting rookie.

“We’d always go at it during practice,” Houston said. “I was a scout team guy in there 90 plays and he’d come in and beat down on me. It helped me learn to take failure in a good light instead of taking it as a downer every team. I don’t like to lose, but when I do lose, I like to learn from it.”

“Him being a freshman, coming in here and trying to jump the snap every time, it really pisses you off,” Andrews said with a smile. “We got into a fight — a tussle — a couple of times. But after that, it kind’ve just built into a friendship. Until he broke my foot during spring ball. Then we just became friends after that. That would be my relationship with Sumner.”

Andrews doesn’t actually blame Houston for breaking his foot, though it was Houston that he was blocking when he broke it. Even that didn’t prevent Andrews from developing a respect for Houston and his work ethic.

“Guys from De La Salle, they’ve always got big motors,” Andrews said. “They can constantly keep going, like (former OSU offensive lineman) Dylan Wynn. It’s something you don’t like to practice against but you’ve got to respect it when he’s on your team at the end of the day.”

Houston is honored to be likened to Dylan Wynn, a former teammate and fellow defensive lineman both at De La Salle and at OSU. In fact, Houston says Wynn is the biggest role model he’s looked to during his time in Corvallis.

“The motor that he had, the strength he had, the intensity he played at: that’s what I want to put into my game,” Houston said.

There’s one other similarity between Houston and Wynn that may not get talked about explicitly very often, but still gets acknowledged. Houston and Wynn are both white, making them somewhat of a minority in college football.

His skin color and forceful playing style led to the nickname “The Great White Buffalo,” given by strength and conditioning coach Micah Cloward.

“He is kinda like a big, white buffalo,” Moore said. “He’s big and hard to move.”

Though he’s received plenty of smack talk from opposing offensive linemen in games for being white, Houston isn’t bothered. In fact, he tries to capitalize on the lowered expectations.

“They think lower of me, which I could take as an advantage because they don’t expect what I’m going to bring,” Houston said. “But once I smack them in the mouth once or twice, that all goes away. Then they play me

just like anyone else.”

It helps that Houston has bulked up at OSU — he’s listed at 6-foot-2, 273 pounds but says he’s closer to 290. Keeping weight on was a struggle in high school because he would play offense, defense and special teams. He entered his senior year at 270 pounds and finished it at 240. He went the opposite direction in his first year at OSU, rising to 280 pounds during his redshirt year.

“(Gaining) 40 pounds in a year — it wasn’t all muscle,” Houston said. “It was a lot of fat. I felt bloated. I was pretty slow and sluggish and had no endurance whatsoever. But now I’ve worked on it, gained an extra 10 pounds and I feel a lot better moving

around with the weight.”

Houston’s new body type took some getting used to. In high school he would play almost every snap without needing a breather; last year, it was “three or four plays, max,” before he was winded. But this season, Houston has felt much better about his conditioning.

“My redshirt freshman year, I obviously was not prepared to play,” Houston said. “I was young and undersized. I’m getting up there and able to hold my own a lot better.”

Of the 80 to 90 plays each game, Houston has been on the field for an average of about 45 this season. Though he hasn’t made a ton of highlight plays, going without a tackle for loss or sack thus far, coaches have lauded his technique. After each game, the coaching staff watches the film and grades each player’s technique and performance on a 0-100 scale. Houston has held his own among other defensive lineman by grading out in the mid-80s and occasionally touching 90.

Houston has aspirations to be a bigger playmaker in his remaining two and a half years at OSU, but he also has big goals off the field.

He’s a Construction Engineering Management major with a minor in Business and he’s currently in his first term in Pro-School.

By his own estimate, Houston spends 14 hours in class each week, 15 to 20 hours doing homework and about 40 hours in football related activities like practices, games, team meetings and film sessions. It’s no surprise that Houston faces a difficult dilemma each week in how to budget time to get everything done. He can’t let his grades slip since he wants to maintain at 3.5 GPA, but football is also a huge priority.

“It’s a full time job plus another full time job,” Houston said.

He handles it by mimicking his no-nonsense football playing style in his time management and school work.

“In the dorms, every night he was up super late with his light on doing homework,” Moore said. “When he told me he was minoring in Business too, I was like, ‘I don’t know how you do it.’ But he gets it done, which is pretty crazy.”

“He’s a smart, smart young man,” Andersen added. “He’s worked hard to get to the spot where he’s at this year.”

After the Colorado game earlier this season, Houston had to do almost seven hours of homework the day after the game and still didn’t finish all his work for the weekend.

“A lot of my work has to be done on the weekends,” Houston said. “There’s a lot of work but I’m balancing it. It keeps me more focused because I have football. I don’t have

time to screw around.”

Houston’s passion for engineering started as a child, when he developed a tendency to take objects apart and analyze their

mechanical nature.

His dream job once football ends: “Get hooked up with a big company, start working on jobs and making some infrastructure

to better the world.”

And if anything goes awry in the meantime like his hole in the wall on his dunk attempt last year, better believe he’ll start patching it up without a moment’s hesitation.

That’s just the way of the Great

White Buffalo.