Oregon State’s Science and Policy club hosts panel discussion

February 3, 2020

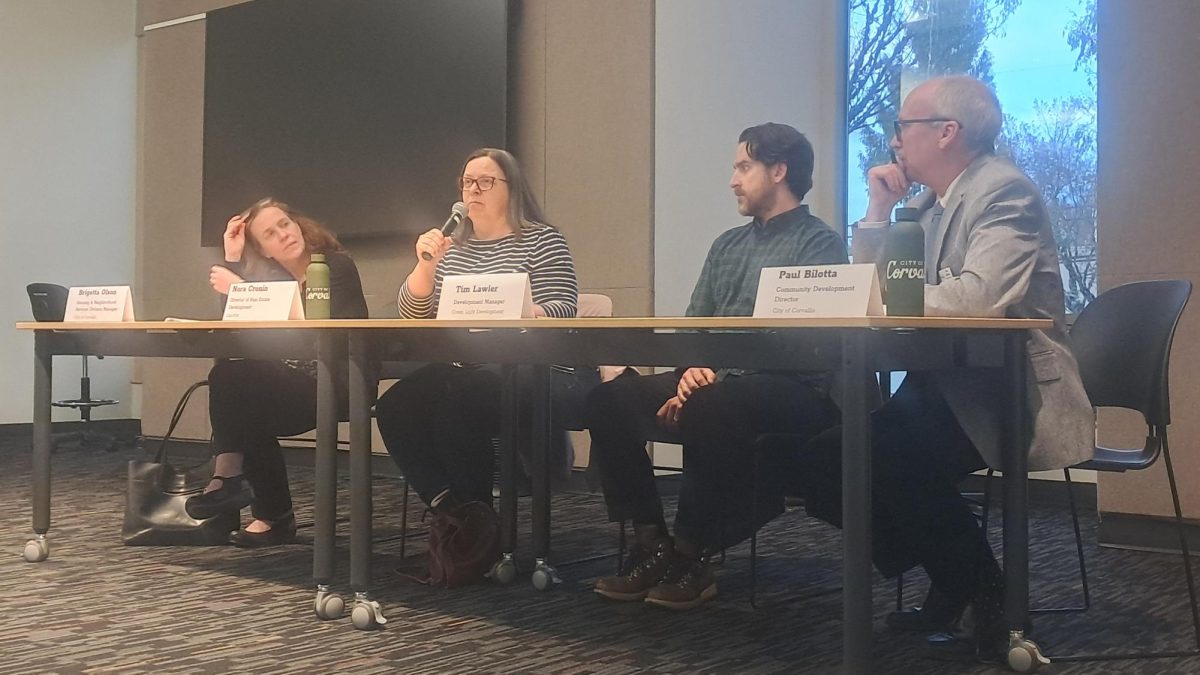

The Oregon State University Science and Policy club hosted a panel discussion, titled “How and Why Should Scientists Communicate with the Press?” on Jan. 29.

This panel was organized by Claire Couch, a fifth-year integrative biology Ph.D student and president of the Science and Policy club. She and her club had created the event because of a general interest in the intersection of science and the press.

“… people were interested in learning about effective media communication, so we were lucky enough to get these amazing panelists,” Couch said. “I’m hoping they’ll be able to share sort of how scientists can engage with media to enact social change.”

The three panelists brought in were Jane Lubchenco, Ph.D, Karen McLeod, Ph.D

and Steven Lundeberg.

Lubchenco is an environmental scientist and marine ecologist and a professor of OSU’s IB 518 Science and Policy course. She has been referred to as “the bionic woman of good science” and worked under the Obama Administration as the chief of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

McLeod is a professor of OSU’s IB 515 Science Communication course: Making Your Science Matter. She is also the deputy director of Communication Partnership for Science and the Sea, an organization that mainly focuses on education surrounding scientific communication.

Lundeberg is a news writer in the News and Research Communications office at OSU, and has worked for news sources in Bend, Klamath Falls, Springfield and Albany for the past 25 years.

Lundeberg said that he was excited to speak at the Jan. 29 panel, and that it was extremely important that students attended the event.

“I think it’s important because communication is the oil that keeps the world working, stories kind of make the world go round, and if you are in a STEM field and doing fantastic work, and probably doing fantastic work that had real applications for bettering people’s lives, it just seems sort of intuitively important that the more people who know about what you’re doing, the more good your work will do, the more people will know about it…,” Lundeberg said.

Kirsten Steinke, a second-year Ph.D student in the College of Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences in the ocean ecology and biogeochemistry discipline, spoke before the event about her reasons for attending.

“I’ve been really interested lately in how science works with policy, so I guess I’m just here to learn more and kind of see where the crossover happens,” Steinke said.

Benjamin Young, another second-year Ph.D student in the College of Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences in the ocean ecology and biogeochemistry discipline, spoke about his interests in the panelists.

“I’ve been interested in science communication, and I think the panelists have a lot of experience with that…,” Young said.

The three panelists answered multiple questions posed by Couch, discussing how media influences public policy, how to ensure your research is accurately represented and the common mistakes made by scientists while speaking to the media. The speakers then opened the floor to questions from the audience, and spoke on combating scientific illiteracy, traversing social media and correcting misrepresentations of scientific findings.

“I think about without communication, without the work of today’s scientists reaching say, kids who are 10 or 12 years old, if what today’s scientists are doing doesn’t in some way reach these kids, we might be failing to inspire the next generation of scientists,” Lundeberg said. “The impact of scientists and their work will be much greater through communication.”

Couch and the Science and Policy club continue to plan future events surrounding communication, policy making and discussion. They urge any student with an interest in science, policy making or communication to join.

Couch said, “It’s open to undergrads and graduate students from any department, but sort of our focus is for STEM students who want to engage with policy and communication… we’re more like a group of science students trying to educate ourselves on how to make our science relevant to policy and to the public.”

![Newspaper clipping from February 25, 1970 in the Daily Barometer showing an article written by Bob Allen, past Barometer Editor. This article was written to spotlight both the student body’s lack of participation with student government at the time in conjunction with their class representatives response. [It’s important to note ASOSU was not structured identically to today’s standards, likely having a president on behalf of each class work together as one entity as opposed to one president representing all classes.]](https://dailybaro.orangemedianetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Screenshot-2025-03-12-1.00.42-PM-e1741811160853.png)