When Tai Stith started a new route for her morning runs in Albany, Oregon, the last thing she expected to come across was a secret lab that held stories of World War II projects and the origin of the titanium industry.

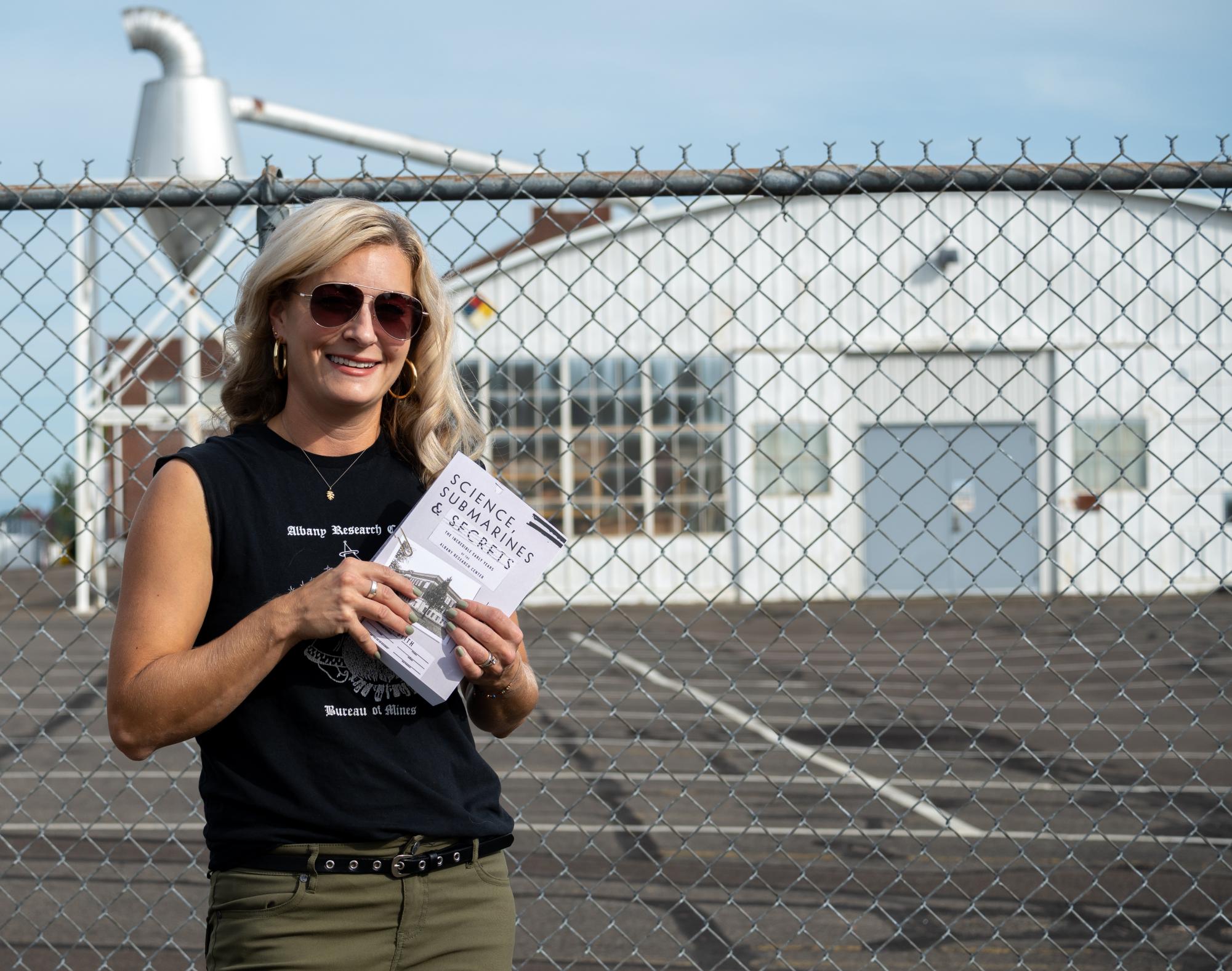

According to Stith, a 2005 graduate of Oregon State University’s graphic design program, she and her husband had just moved to southwestern Albany when she noticed the facility that would become the inspiration for her book: “Science, Submarines and Secrets: The Incredible Early Years of the Albany Research Center.”

A high fence surrounded the perimeter of the complex and, according to Stith, the property was patrolled 24/7 by a security guard. Having also studied architecture during her time at OSU, Stith took notice of the turn-of-the-century brick buildings inside the fence and the industrial WWII-style warehouse alongside them.

“That building tipped me off to thinking that there was probably some pretty significant history to this place,” Stith explained. “But more than just the visuals of what I saw within that fence. There is an energy that came from this place that was unreal, and I can’t even describe it … it was like this place was calling out to me to find out its history, and I couldn’t ignore it…For the longest time I tried to, but one day in 2011, it was the first day of spring break. It was a foggy, gloomy day. I was doing my daily route … I thought, I have to start looking into this. I can’t ignore this any longer. What is this place about?”

“Science, Submarines and Secrets” is the story of not only the Albany metals industry, but also a metallurgist and “father of commercial titanium,” William J. Kroll, who escaped Nazi occupation and arrived in the United States having already patented the manufacturing of titanium and alloys.

“(Kroll) is why we have aircraft, and all sorts of high tech innovations with titanium,” Stith said. “He made it possible for titanium to be made in large quantities and inexpensively. So he came to Albany and he started working on zirconium, which a lot of people don’t know anything about zirconium.”

Along Kroll’s journey, Navy Captain Rickover, convinced the U.S. government to begin research on a nuclear powered submarine.

“We could have a real true submarine that could stay underwater for an unknown, basically unlimited amount of time, by using nuclear power as its engine,” Stith said. “So (Rickover) worked closely with Dr. Kroll, who was here in Albany, on developing parts for the world’s first nuclear submarine. Overall, the best part of this book to me is that it showcases how the right people were in the right place at the right time to make not just zirconium, but hafnium for the world’s first nuclear submarine, everything fell together like this beautifully designed puzzle.”

When Kroll was fired from his lab, he became a professor at OSU from 1951-1961. The fountain at the back of the Valley Library was dedicated and donated by Kroll. Kroll also worked heavily with Henry Gilbert, the son of E.C. Gilbert, Gilbert Hall’s namesake.

Gilbert, who worked at the Bureau of Mines in Albany, helmed some major advancements in furnace technology.

According to Stith, National Energy Technology Labs (previously called the Albany Research Center), is Oregon’s sole national laboratory. They work on nuclear solutions, energy solutions and innovations in new fuel types alongside other national labs.

Alongside the main lab, NETL now has a 42-acre complex in Albany that includes centers like The Advanced Alloys Signature Center, an alloy research and development facility, and the Severe Environment Corrosion Erosion Research Facility for simulating high temperature and high pressure environments, among other things.

When doing Stith’s initial research, nobody could give her clarity on what exactly the property was, or what had been done there.

She had all sorts of theories: metals research, connections to the Manhattan Project, mysterious cancers cropping up in the neighborhood.

Stith turned to the internet, where she found documentation of a 1980’s cleanup of radioactive contamination on the site and plutonium found in the soil.

“I was like, wait, what? That doesn’t just happen, you know, by accident,” Stith said. “Something was worked on there to put the plutonium in the soil. Amongst (other substances), uranium was found in the soil, thorium, radium.”

This kickstarted a 10-year journey of hunting down declassified documents and talking to former employees. She was even able to make the right connections to go on site and take photos of the lab.

But even up to 2019, Stith said she wasn’t ready and, in fact, she had to be convinced to officially write the book.

“I previously had four or five young adult fiction novels that I had done, but no nonfiction,” Stith said. “So it was as daunting a task as I thought it would be. Even harder than I thought it would be. But by March of 2022, I had a completed book that was published.”

Stith never thought she would be writing history books, but the COVID-19 pandemic gave her the opportunity to really work on the project despite wrangling three kids at home.

“Even today, like I drove past the lab, about a year ago, and I thought, how preposterous is this, that I somehow was able to write a book about this,” Stith said. “And the funny thing was, every time I tried to put the project down … something had happened to draw me back in.”

Now Stith is working on the sequel to “Science, Submarines and Secrets.”

“It’s just as daunting as the first book, if not more, because there’s so much secret stuff that I don’t think I’ll be able to find what I need, but I’ve been surprised before.”

The sequel will begin where its predecessor left off: in 1957, when the lab’s first major project was over and they were “finding their feet” once again.

“I have an inkling that one big driving factor behind what was going on in the laboratory were the secret projects going on with the Atomic Energy Commission,” Stith said. “And I have a very strong hunch that the secret work that was done out there had a lot to do with our advancement of our nuclear knowledge.”

Stith’s other books include The Hadley Hill young adult mystery series, The Fulbeck Six mystery series and the Wugawanda children’s books.

The Albany Regional Museum has an interactive exhibit, Albany’s Specialty Metals, where visitors can look at, and touch, some of the metals like titanium and zirconium in person and read about some more of the history surrounding the local metals industry.