Epidemiologist emphasizes context when looking at COVID-19 statistics, models

March 30, 2020

As the number of COVID-19 cases in America continues to climb, contextualizing statistics like the case fatality rate and doubling time help accurately show the severity of the virus and the importance of limiting its growth.

Two important statistics epidemiologists use to model virus severities are the mortality rate and the case fatality rate. The two statistics are similar but have separate implications.

People don’t need to test positive for COVID-19 to be included in mortality rate statistics since it is calculated as the total number of deaths divided by the total number of people in a population. The mortality rate is best used to determine an illness’ impact across an entire society.

The World Health Organization defines the case fatality rate as, ‘the proportion of reported cases of a specified disease that are fatal within a given time frame.’ Only cases that test positive for COVID-19 are included in these figures since it is calculated by dividing the number of deaths by the number of people who have tested positive. The case fatality rate is more useful in judging the exact severity of a disease, given that someone has already tested positive.

There are currently around 110,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the U.S., with over 1,600 of these cases resulting in deaths. This would put the current overall mortality rate at around .0005%, or about 1 in every 204,000 people.

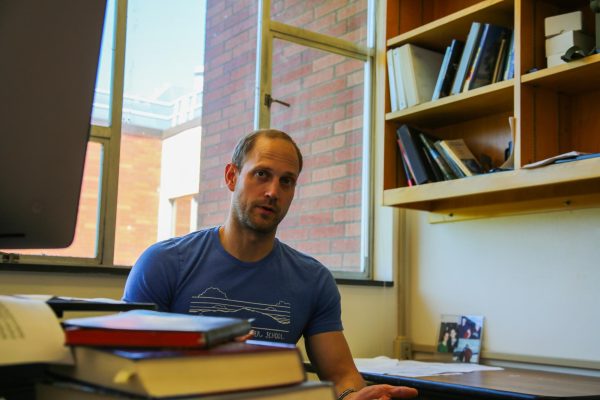

According to Benton County epidemiologist Peter Banwarth, the case fatality rate provides clearer information on the true severity of the virus. The current case fatality rate of COVID-19 is at 3%, 30 times more lethal than the common flu. However, this statistic needs a proper contextualization as well.

“One thing we know very well is when an individual has died of COVID-19. They have almost certainly been hospitalized, they have almost certainly been tested, we know that they have contracted the disease and we usually know that it was the cause of death,” Banwarth said. “One thing that is not known very well is how many people have COVID-19 but have mild symptoms. Among confirmed cases of COVID-19, we estimate that about 80% of people that contract it show mild or no symptoms. They might not be tested at all.”

In the case of a novel virus such as COVID-19, the case fatality rate will often overstate the true number. It’s likely that many asymptomatic carriers of COVID-19 will never know they had it all, and will never receive the test for it. However, an inflated case fatality rate doesn’t dismiss the severity of COVID-19.

Like many other emerging infectious diseases of the past, COVID-19 exhibits an exponential growth rate. This doesn’t mean that the virus spreads incredibly quickly, but rather that the growth rate is multiplicative. Epidemiologists often measure the spread of a virus through a statistic called the ‘doubling time,’ which refers to the time it takes for the number of positive cases or deaths to double in size. The number of COVID-19 deaths in the U.S. doubles about every two and a half days, while Oregon’s has doubled at a rate of about once a week.

“The growth can start very, very slow, and can stay slow for a while. [At some point] it hits an ‘elbow’ and starts to go up much faster… the real question is when public health is going to be able to bend that curve,” Banwarth said.

Inflection points are the point in a model or line where the curve changes direction. In the context of COVID-19, that point will be reached when the rate of new cases sharply increases. Banwarth suggests that Oregon hasn’t reached this point yet.

“Models are showing that with poor shelter-in-place, that inflection point would be reached in roughly mid-April. With really good shelter-in-place, we’ll never reach that inflection point. It’s so dependent on how effective our control measures are,” Banwarth said.

To assist efforts in bending the curve, Gov. Kate Brown issued an executive order on March 23, imploring Oregon residents to stay home unless cleared for specific exceptions. Violators can be assessed with a Class C misdemeanor, which is punishable by up to 30 days of jail time and a $1,250 fine.

These measures were put in place in an attempt to mitigate the potential damage COVID-19 could do on the state’s population. There are a finite number of hospital beds, ventilators, and personnel available to provide assistance. Oregon currently has 715 available ventilators and a total of 2,654 hospital beds. If the amount of patients requiring intensive care exceeds the number of available beds, tough decisions have to be made on who receives treatment.

According to Banwarth, it’s uncertain when the effectiveness of shelter-in-place policies will be known. A majority of positive COVID-19 cases don’t display any severe symptoms, and the average incubation time is five days. This drastically increases the risk of healthy carriers spreading the disease while in public.

“The challenge right now is for the next two to four weeks, we aren’t really going to be able to tell if we are on an exponential curve before we hit that inflection point, or if we’re being successful,” Banwarth said. “We’re going to have to recognize that we know scientifically it works, and it takes a while to show whether or not it’s working, so we have to do it anyway.”