Ask Dr. Tech: Why textbooks should be free, changes in production

February 3, 2016

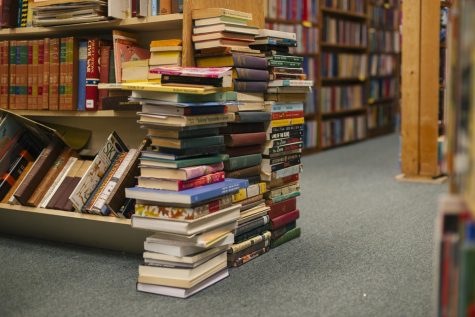

Learning is priceless, education is expensive and ignorance is even more costly but what is a student to do when tuition, housing, textbooks, technology and the cost of living present barriers to attaining academic success?

Savvy students study a situation and take action on the points that may create change. That is what ASOSU leadership has done in collaboration with Open Oregon State and allied faculty.

The Fall 2015 “Rally for Free Textbooks” heralded a major change in how textbooks are created and assigned.

Imagine a world in which your course texts are downloadable online for free and available in print copy for $10-$30.

I’m talking about big books like biology, chemistry and calculus.

This change is happening nationally and in order to understand its dynamics I spoke with Dianna Fisher, Director of Open Oregon State. In addition to managing OSU’s open educational resources (OER) she spearheads the effort to facilitate the writing, review and adoption of open textbooks.

“Open textbooks” are educational materials that may be acquired by readers without cost and are typically licensed to allow instructors to revise them.

Fisher has a vision: “In a perfect world all courses at OSU will have no-cost open textbooks.”

That is not wishful thinking on her part because in 2015 the Oregon Legislature allocated $700,000 to support open textbook initiatives in which OSU is a strong player.

Fisher has the will and smarts to turn these ideas into action and she has the visible support of OSU leadership including President Ed Ray, Senior Vice Provost of Academic Affairs Brenda McComb, Vice Provost of Information Services Lois Brooks and Associate Provost of Outreach and Engagement Dave King.

The Beaver Store is already ahead of the curve on supporting open textbooks as Academic Materials Manager James Howard told me: “The Beaver Store is non-profit so runs our textbook business as a cost recovery and will distribute free content as requested by instructors without a problem.” Howard is no novice to these issues as he recalls a conference on the distribution of digital content in 1994.

That is the year that I launched my philosophy course on the Web, InterQuest (PHL201), which was built entirely with public domain texts and my own writing. Winter 2016 is my 87th term of teaching InterQuest on online and I have never use a textbook that my students had to buy. Wisdom does not have a price point and Plato is not around to collect royalties anyway.

So what could possibly go wrong with free textbooks? To explore another side of the issue I put that question to Dr. James Kourmadas, Lecturer in marketing at William and Mary College.

Kourmadas spent a decade working for the prominent textbook publisher McGraw-Hill Higher Education and has been featured in numerous articles about open textbooks and digital learning materials.

He pointed out two complicated issues in the open textbook movement: free textbooks are not really “free” and quality assurance is an unsolved problem for open textbooks.

Kourmadas agrees that new hardcover print textbooks are not realistically priced in the contemporary market because there are many ways of delivering texts to lower costs all-around.

Yet it is erroneous to suppose that open texts books have no costs associated with them. It takes time and money to write, produce and maintain all books. The necessary costs of open text books are factored into tuition fees and taxes.

It is one thing to subsidize the creation of a textbook, but with the rapid change of knowledge in all disciplines there must be an ongoing effort to update textbooks in order for them to remain relevant for contemporary learners.

As Kourmadas observes: “the books will need to be revised and maintained on an ongoing basis which would require either some sort of government agency to manage the process or some sort of public/private partnership with an industry partner with expertise in Higher Education.”

It is not immediately evident to me that a government textbook publishing system will be more efficient and effective than the existing commercial textbook publishing system.

Whatever a textbook costs, its worth depends on its accuracy and effectiveness as an educational tool.

Commercial publishers of books and journals have long-established mechanisms of quality control via peer reviewing in which experts in the relevant areas read and evaluate drafts of the proposed materials.

Books and papers that do not pass the review stage do not get published. This peer review process is an important part of academic scholarship overall, providing quality control through fact checking and informed critique.

As Kourmadas puts it: “The industry acted as the mechanism to seek out the best and brightest instructors nationally, invest in their ideas (often over 3-5 years before seeing a sale), run a national peer review system to vet the ideas and content, and build the products for instructors to use. The beauty of this system is that it is completely aligned with academic freedom; publishers take the risk to develop the products and since they are an outside party, they have no authority to make anybody in any university use them or students buy them.”

These traditional controls on content change when public agencies control the publishing process.

Of particular note are the implications of an internal relationship between the publishing of open textbooks and their adoption for courses.

When the universities which do have authority to require specific texts also control the content of those texts the power relations in higher education have changed.

There is more than one sense of the word “free” involved when thinking of free textbooks.

These are important issues to discuss openly as we move boldly toward government produced educational materials for public universities.

OSU’s Diana Fisher is aware of these concerns and responds that the main issue with textbooks is that of social equity; “We want students to make their choices based on learning value, not economics.”

That is a powerful motive for social change and the movement to free the textbook is certain to occasion waves of change at OSU for years to come.

The opinions expressed in Dorbolo’s column do not necessarily reflect those of The Daily Barometer staff.