OSU researchers speculate dietary choices may affect likelihood, treatment of breast cancer

October 22, 2017

Specialists work to better portray breast cancer-related findings to general public.

By the end of this year, an estimated 252,710 women and 2,470 men will be diagnosed with breast cancer, according to the American Cancer Society. 40,610 of those women and 460 of those men will die from it. Breast cancer is 100 times less common in men than in women. For women in the United States, it is the second most common type of cancer. It is the most common cause of cancer-related deaths among women globally. Older women are more at risk for it, but this does not mean that anyone is immune to it.

October is National Breast Cancer Awareness Month. Oregon State University faculty members are focused on the variety of factors that may affect navigating the healthcare setting, getting a screening and living with a diagnosis. The research these faculty members conduct could save a person’s life.

These faculty members are doing their part to raise awareness through research on how diet, being a minority or being an immigrant affect breast cancer treatment. According to Veronica Irvin, assistant professor in the College of Public Health and Human Sciences, she has focused her research on how the way information is presented influences decision-making, some of which involves breast cancer.

“I look at health literacy, the degree to which people can obtain, communicate and understand basic health information and services to make appropriate health decisions. Are people familiar with the terminology and how it is displayed? Who is the source?” Irvin said. “I’m working on looking at all the websites in the counties (of Oregon) and examining if they talk about mammograms, what recommendations are given and what language is provided.”

According to Irvin, she has been coding the websites of clinics that offer mammography screening throughout the state and examining what information they present to women. She is interested to learn if information is less available or poorly described in rural vs. urban areas and if this difference could explain differences in screening rates in these countries.

“There’s been prior research that shows that women who might be disadvantaged in some way may not be told all the health care options because it may be presumed that there’s only certain procedures or treatments they would be able to complete because of their resources,” Irvin said.

Some of the other work she has done involves a local clinic in Albany that sees clients who do not have insurance, according to Irvin. Her research involved working with their clinic manager to evaluate how a bilingual, bicultural navigator helps Latina patients. These are patients whose first language may not be English, or who are unfamiliar with the U.S. healthcare system.

“We did an evaluation to learn what were women’s impressions of the mobile mammogram and what happens afterwards. I was looking at how a navigator helped women not only at the screening day, but also completing follow-ups and understanding lab results through the entire treatment process, or until they were determined to not have cancer,” Irvin said.

Previous research shows that it takes Hispanic women and African-American women longer to have their cases resolved, according to Irvin. It may take longer for them to get an appointment or to gain access to the clinic, for various reasons. A lay navigator has been shown to improve cancer care by possibly alleviating these barriers. Although breast cancer screening is important, there is no cure that comes from screening alone. The really important part is what happens after the initial screen.

“It’s not so much the screen as it is to get treatment as soon as possible once it is known that you have cancer. That is what saves lives,” Irvin said.

Encouraging women to get screened is only part of the battle, according to Irvin. The other part is making sure that the necessary follow-up care is completed in a timely fashion.

According to Dr. Mehra Shirazi, assistant professor of Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, refugee and immigrant women in the U.S. struggle with a variety of factors when trying to access health care services.

“Poverty, environmental risks, racialization, discrimination, social isolation, lifestyle changes and health care access are often contributing factors. There is also an information gap on health disparities due to lack of explicit data on ethnicity and country of origin,” Shirazi said in an email.

According to Shirazi, her focus is on community-based participatory research that strives to get rid of the barriers, mainly socio-cultural, that prevent refugee and immigrant women from getting early screening and accessing the resources that could save their lives.

“CBPR methods can increase our understanding of risk and protective factors in refugee and immigrant communities and contribute to development of culturally appropriate programming to address health disparities,” Shirazi said via email. “My use of CBPR has taken an innovative approach to addressing health disparities and building evidence-based community health programming.”

In a study with Afghan immigrant women in the U.S., results showed that those immigrant women have a low awareness of breast cancer risks and early detection screening is not as accessible for them, according to Shirazi. This makes them more likely than white women in the U.S. to get a breast cancer diagnosis once it has developed to an advanced stage.

“This study was the first of its kind to look at breast health views and knowledge in this specific population,” Shirazi said in an email. “Rather than applying a one-size-fits-all approach, as a result of this work we developed a successful, culturally tailored breast health education program that used alternative approaches through innovative means of communication, as well as culturally sensitive, bilingual-trained health navigators to increase knowledge and awareness around breast health and to efficiently connect the women to cancer screening services.”

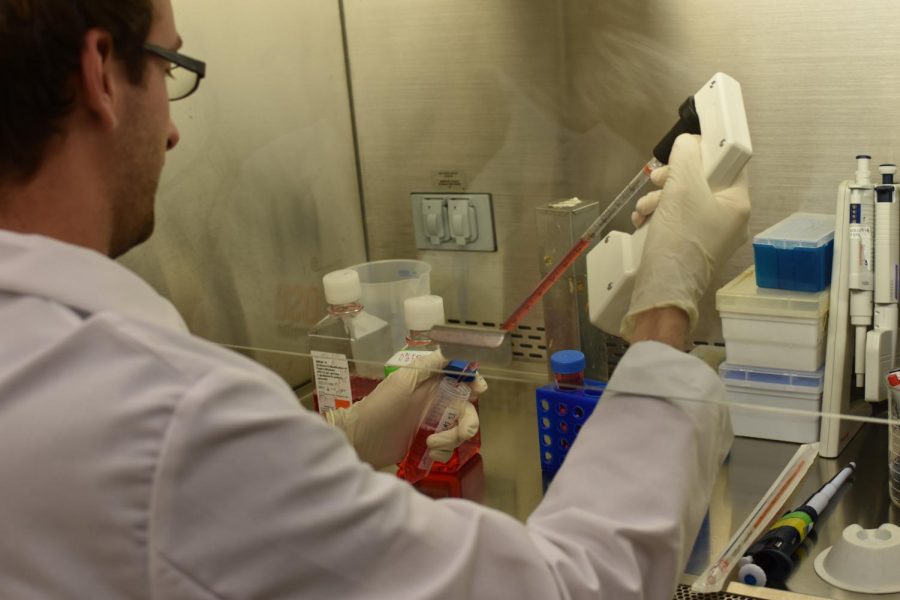

According to Emily Ho, director of the Moore Family Center (which is located in the College of Public Health and Human Sciences) and an investigator in the Linus Pauling Institute, her research program attempts to understand how diet can prevent cancer and slow down the growth of cancer cells. There are a number of leading cancers in the U.S. that are impacted by diet. Breast cancer is one of them.

“If you look at the data over the last couple of decades, imbalances in diet contribute to more cancer than does smoking,” Ho said. “It could be things in our diet that are cancer promoting, but it’s also things that we are lacking in our diet that are going to be contributing to cancer as well.”

World-wide data shows that the U.S. is number one in terms of incidences of breast cancer in women in comparison to other countries. For example, Asian countries have far lower rates, according to Ho. Because of this, Ho has been investigating how the American diet and lifestyle choices may be contributing to this high rate of breast cancer in the U.S. Her recent research has involved investigating the compounds in cruciferous vegetables, such as broccoli or cabbage, that may have cancer-fighting properties.

“We’ve done a lot of studies in cells and models to show that (these vegetables) help prevent and slow cancer through potential mechanisms,” Ho said. “We’ve done a small clinical trial in breast cancer patients where we were able to show that if we were to show that women supplemented with an extract of broccoli had slower markers for cell proliferation in some of the women.”

Nutrition is the biggest part of one’s health that can be controlled, according to Ho. There are many dietary components that impact breast cancer, so diet is most definitely something that every woman should pay attention to, whether they’re more at risk than others due to family history or not.

“With breast and prostate cancers, because they tend to be slower growing cancers, there’s potentially a lot of time to use diet to slow it down,” Ho said.

One way that Ho and the group she works with in the Moore Family Center make an impact is by offering cooking classes to students and children so they can learn the importance of eating a healthy diet.

“For us to cure cancer there’s a lot of things that we need to do. There’s the researchers, there’s the health professionals, but I think there’s also the societal piece. People need to take ownership of their health as well,” Ho said. “I think how you treat your body with nutrition, exercise, just taking care of yourself, has a huge impact not only on your disease processes, but on your mental and overall well-being.”

According to Ho, a big struggle for her and her research team is making sure the correct information gets to the masses.

“A lot of people are relying on the internet for their nutrition information. There’s a wide variability of quality content,” Ho said. “It’s really difficult for the average person to be able to sift through what is good information and what is not. As long as Dr. Oz says it’s okay, that’s good enough for some people. It’s a challenge.”

There has to be a balance between research and communication to keep raising awareness about breast cancer, according to Ho.

“We have solid research in nutrition, but there’s still the communication piece missing. In the last decade people have been looking more to nutrition as a way to manage their health, but there’s so much misinformation out there,” Ho said.

According to Irvin, it is one of her goals to ultimately achieve making research accessible and relatable to the average person so that it can make an impact. She works closely with the communications office to share her results with the community and get information to the mainstream media.

“In science, we don’t do as good a job at making our findings interesting to the masses. It doesn’t get translated as well. What I’m striving for is making research relatable to the average person,” Irvin said. “As researchers, we’re trying to write our findings in lay version, a version that’s easier for others to understand. It’s not one thing makes a change. It’s multiple pieces of information together.”