Hanna Royer is deaf and brings a “no excuses” attitude to the color guard

December 5, 2016

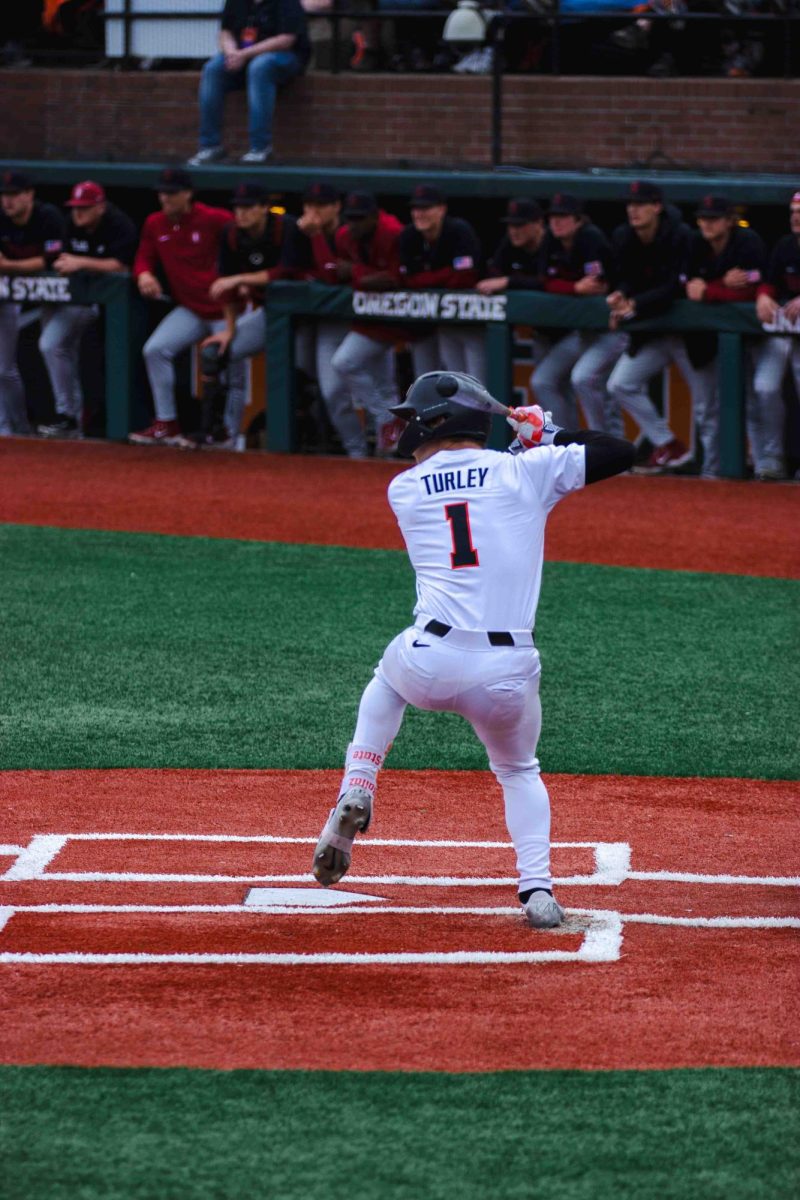

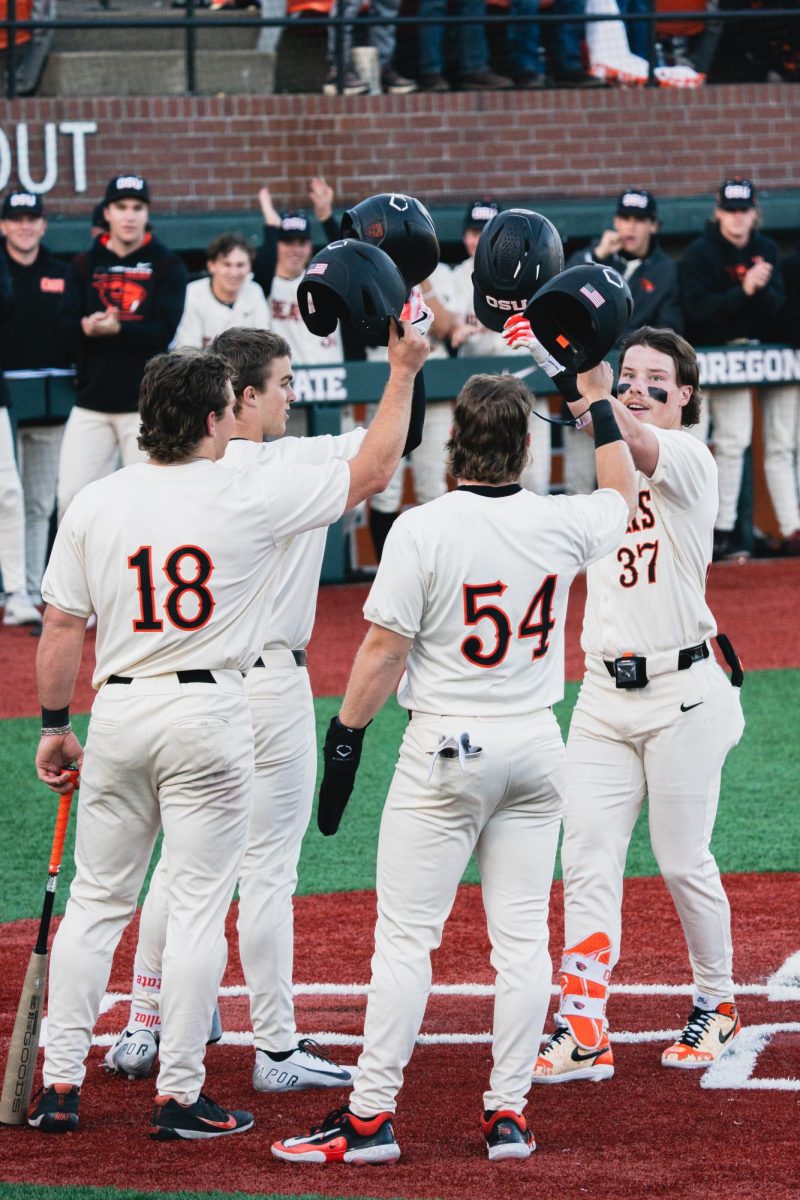

The Oregon State University Marching Band parades into Reser Stadium and emerges onto the field. The horns blare and overtake the roar of the spectators. The pop of the snares fill the cracks in the crowd’s voice and the bass drums demand attention; the marching band provides the rhythmic heartbeat of Beaver nation.

Orange and black flags swing through the air in time with the music. The whole performance is tight, and well rehearsed. A good ear, some coordination, a sense of rhythm and lots of practice are what you need to contribute as a member of this team.

The entire routine seems reliant on the tune. Take away the sound, and one might imagine the entire act falling into disarray. However, silence does not impede color guard member Hanna Royer, who is deaf.

“It is just barrier in my life, but I do not let my deafness stop me from doing anything,” Royer said.

Royer’s game day begins five hours before kickoff with a final practice, followed by performances for tailgating fans around campus. Royer’s journey with the color guard didn’t start with game days though; it started five years ago, and her history with music runs even deeper.

Royer grew up in Albany and transferred to OSU this fall to study history. Hanna has been adapting to her deafness since she was young. Her mother, Nikie Strahan, learned of her deafness when she was just one year old, and it was a shock.

“I didn’t know what was going to happen to her, but it was very scary as a parent,” Strahan said.

Strahan began learning American Sign Language as soon as she received Royer’s diagnosis, later teaching her and her brother Tyler.

“It wasn’t until two and a half (years) that we were finally communicating with sign language,” Strahan said.

Royer recalls early and constant support from her mother.

“My mom always told me when I was growing up that I could do anything,” Royer said. “And my deafness should not stop me.”

“I never told her no because whatever she went for, she succeeded in,” Strahan added.

Royer was inspired to join her middle school band after her brother suggested deafness prevented her from playing an instrument. She wanted to prove him wrong and ended up playing the flute. She continued with band at Sprague High School in Salem, where her band director later encouraged her to join Sprague’s color guard. Jordana Buyserie, a friend of Royer’s, is also deaf, and joined the OSU Color Guard this fall.

Color guard member Ryleigh Childers remembers when she first met Royer at band camp this September.

“I was excited to see Hanna come in with interpreters, I was actually just excited to get to learn some sign language,” Childers said.

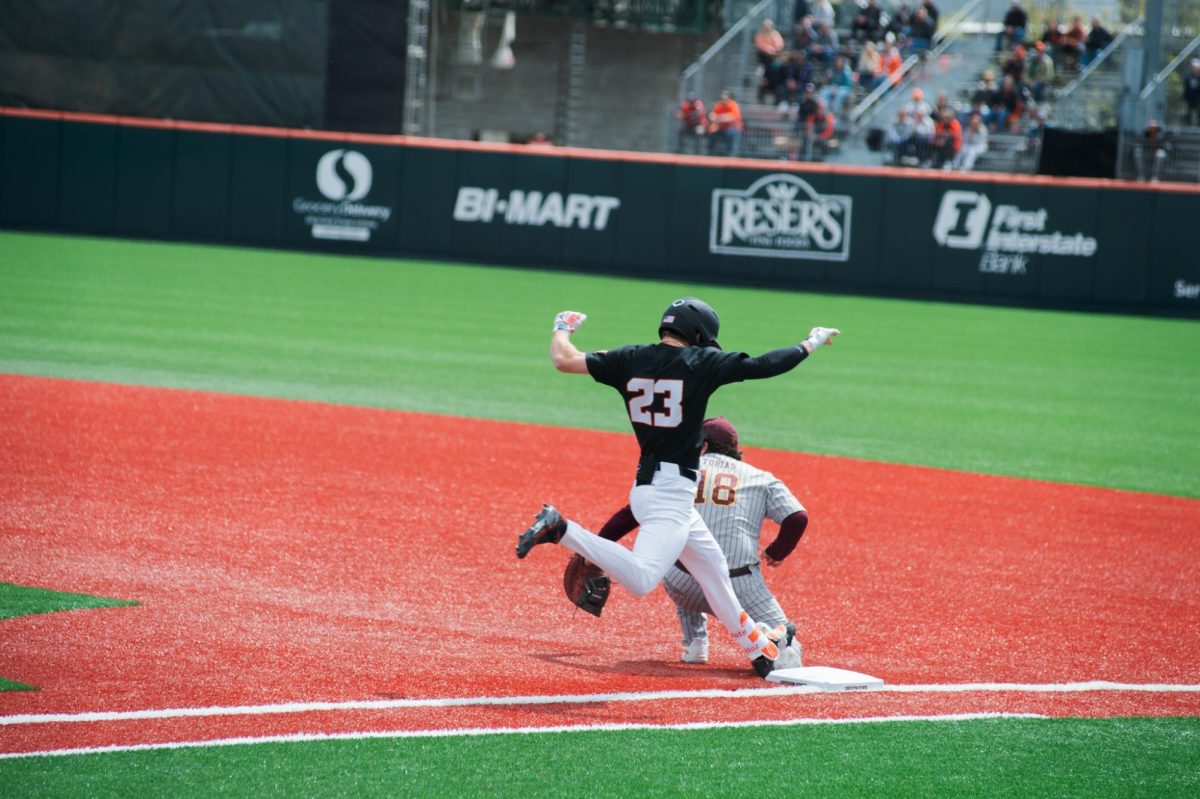

Familiarity comes in handy in the color guard, she and her teammates have developed solutions for keeping time with one another. Additionally, interpreters are on the sidelines during performances, helping keep time for Royer to ensure she makes every mark in sync with the team.

“The interpreters count for them on the sidelines, but in spots where interpreters can’t get close to the drill, one of us will hold the flag in one hand, while counting off on the other,” Childers said.

“It is a challenge,” added Royer. “But I have learned how to deal with it by having the color guard girls come up with some hints during performances so I can be on time with everybody else.”

The team was enthusiastic when Royer joined the team, and developing on-the-field cues and hints has brought them closer. Royer has even taught her teammates some signs so they can communicate easier.

Talie Oakley, another new member of the color guard, said adjusting the team’s communication style was relatively simple.

“I wasn’t sure how to act at first,” Oakley said. “But learning sign language has been so much fun.”

However, not all of Royer’s transitions at OSU have been so smooth.

Royer mentions that the greatest difficulty so far at OSU hasn’t been in the classroom or on the field, but living with people she doesn’t know well.

“The people I live with do not know sign language, so we have to really work on trying to communicate with each other,” Royer said.

Joining Royer in class are interpreters, who ensure she misses as little verbal content as possible.

Deb Kropf, an interpreter from Disability Access Services, worked with Royer in two of her courses this term. She explains that the her job as an interpreter isn’t to be a personal assistant to Royer, as some mistakenly view her role. Kropf explains that her role is to interpret the content of the class or activity, specifically the lectures and conversations which Royer is a part of.

“Really, I’m helping the instructor as much as I’m helping the student,” Kropf said.

Her role is to act as a bridge between Royer, instructors and peers.

Notetakers also provide her with resources to review and study. For Royer, deafness isn’t a disability, but a barrier that can be overcome. Royer doesn’t make excuses and she has become comfortable with many different methods for communicating with others throughout her day. When ordering food on campus, it can be as simple as writing her order down on her phone, or writing with pen and paper. With her cochlear implants, it isn’t always imperative to sign with people, and she’s spent practically her entire life learning to read lips. Royer’s “No Excuses” attitude is clear with even a brief interaction.

“I admire Hanna’s patience, always doing her best and putting in extra effort,” Oakley said. “If I were deaf, I don’t think I would have been able to persevere and overcome being deaf. Hanna is able to fight and succeed.”

At this point, Royer has practiced enough that she knows precisely how to work with others to accomplish activities in the classroom, around campus and on the field. A couple of the interpreters at OSU worked at Sprague when Royer was in high school. Having this history with Royer helps in classes, as they can predict what she might say and are familiar with her signing style. The relationship between interpreters and deaf students can grow quickly, as it has for Royer and Kropf.

“I appreciate her authenticity,” Kropf said. “She has a natural ease with people.”

Occasionally, there are things that the team will find funny because of the signs, humor that wouldn’t land in English.

“I’m sometimes surprised by the random things we connect together about,” Kropf said. “Like the humor we find in mundane, everyday things.”

Royer loves performing for the fans as a member of the color guard, and the joy it brings to her life is impossible to miss.

Royer’s love of music shines as well. Her favorite part of color guard is the drum line.

“There are some times when I am very close to the drum line and I love it because they are very loud and the bass drums give out a lot of vibrations.”

Royer hears music in a different way than many folks, but those vibrations are one thing everyone can feel.

“Hanna has proved to me that if you set your mind to it, there is nothing you cannot do,” Childers said.